‘Blue Serge’: Serge Chaloff’s Baritone Sax Blow Out

On his 1956 album, the bebop saxophonist was joined by East Coast jazz stars Sonny Clark and Philly Joe Jones.

Standing at over 3’5” tall and weighing up to 20 pounds, the unwieldy baritone saxophone has never been as attractive to jazz musicians as the leaner, more glamorous alto and tenor varieties. Even so, there have been some notable masters of the instrument, beginning with the great Harry Carney, a long-time member of Duke Ellington’s band. Other well-known baritone specialists who made their mark on jazz history were Gerry Mulligan, Pepper Adams, Leo Parker, and Serge Chaloff. The latter’s career was exceedingly short; Chaloff died in 1957, aged 33. As a consequence, his discography is small, consisting of just four solo albums. But one of them, 1956’s Blue Serge, is a hard-bop classic that has kept the saxophonist’s name alive.

Born in Boston in 1923, Chaloff was immersed in music as a youngster, learning the piano and clarinet. But when he was twelve, he became obsessed with the baritone sax after seeing the aforementioned Carney play with Duke Ellington. Later smitten by bebop’s complex musical language – and particularly the ornate solos he heard alto saxist Charlie Parker play – Chaloff translated modern jazz’s vocabulary to the baritone. “He could play (it) like a tenor sax,” recalled his brother. “He played it high…The only time you knew it was a baritone was when he took it down low. You couldn’t believe the speed he played.”

Chaloff became famous when he joined clarinetist Woody Herman’s Second Herd in 1947, which eventually led him to make his own records. Beginning in 1954, he recorded for producer George Wein’s Storyville label before signing with Capitol Records. His debut for the Hollywood label was Boston Blow-Up!, which despite its title was a carefully prepared record helmed by the noted West Coast bandleader/arranger Stan Kenton.

In 1956, Capitol invited him to make another record. This time, the baritonist desired a more spontaneous session. “I decided to make a record just to blow,” he recalled. “I picked out what I felt was the best rhythm section around and just told them to show up…no rehearsals…no tunes set…and trusted to luck and musicianship.”

Click to load video

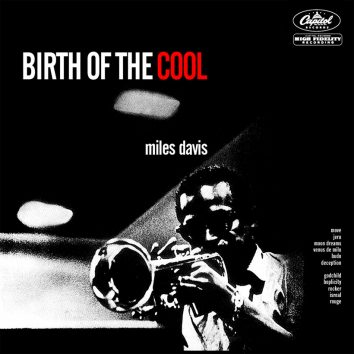

Chaloff’s sidemen were musicians he had never played with before: The Oregon bassist Leroy Vinegar then rising to prominence on the LA session scene, and from the East Coast, pianist Sonny Clark and drummer Philly Joe Jones. Clark was enjoying a successful solo career at Blue Note Records while Jones occupied the drum stool in the Miles Davis Quintet.

“Not having rehearsed together, we were naturally a little bit stiff,” confessed Chaloff, recalling their first session together, which took place one afternoon in March 1956. To help loosen up the musicians, Chaloff revealed that his producer Bill Miller “dimmed the lights way down low to make it more like a nightclub.” The trick worked, helping the musicians to relax and feel at home.

The quartet cut eight tracks in two days, mostly songs from the pages of The Great American Songbook. The session’s highlights included hard-swinging takes on the jazz standards “All The Things You Are” and “How About You” showcasing Chaloff’s athletic precision. Other standouts came in the shape of “The Goof And I” – a revamp of saxophonist Al Cohn’s bebop burner – and the equally lively “Susie’s Blues,” an original Chaloff number.

Click to load video

In addition to his undeniable technical brilliance, Chaloff showed a delicate side with the nostalgic ballad “Thanks For The Memory,” where his soft and feathery tone was punctuated by occasional descents into the lower register. At the end of the sessions, Chaloff was elated. “We were shooting for an impromptu feeling and we got it,” he enthused. “I couldn’t be more pleased.”

Sadly, Blue Serge was the final chapter in the baritonist’s tragically short career. Sixteen months later, Chaloff – once described by the eminent jazz critic Leonard Feather as the “No.1 bop exponent of the baritone” – died from spinal cancer. Thanks to the magical jazz alchemy he conjured while playing with Sonny Clark, Leroy Vinegar, and Philly Joe Jones on Blue Serge, he will never be forgotten in jazz circles.