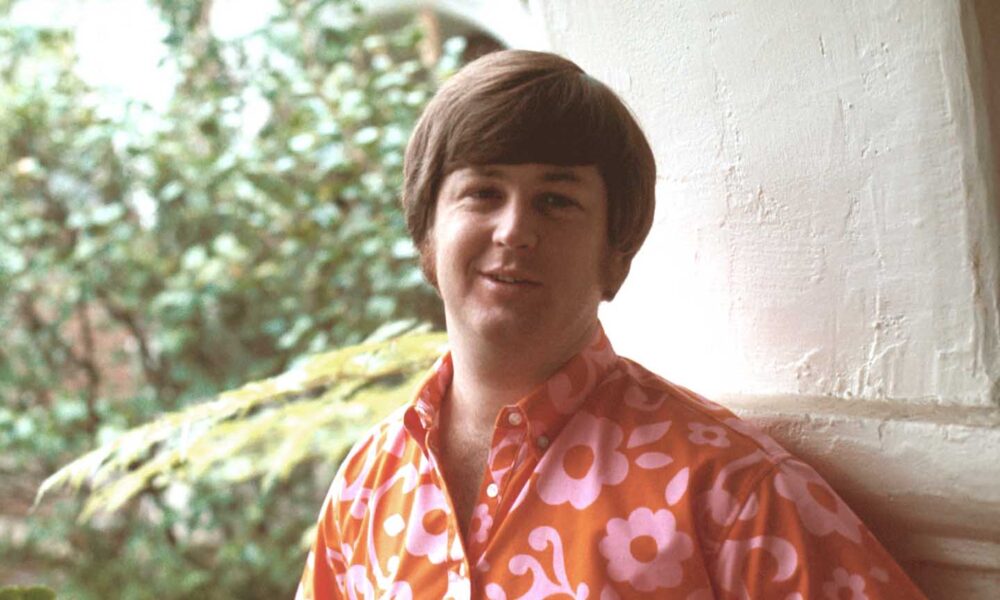

Brian Wilson, Founding Member Of The Beach Boys, Has Passed Away

The pop music mastermind was 82 years old.

Brian Wilson, a founding member of The Beach Boys, has passed away. He was 82 years old.

Earlier today, the following message was posted on Wilson’s official Facebook page: “We are heartbroken to announce that our beloved father Brian Wilson has passed away. We are at a loss for words right now. Please respect our privacy at this time as our family is grieving. We realize that we are sharing our grief with the world. Love & Mercy.” In a statement, Lucian Grainge, Chairman and CEO of the Universal Music Group, said, “Brian Wilson was one of the most talented singer-songwriters in the history of recorded music. Not only did his songs capture the spirit of youth, joy and longing in ways that still inspire millions of fans around the world, his innovative work in the studio transformed the way musicians record even to this day. Brian made an indelible mark, and our thoughts are with his family in this time of loss.”

Wilson was born in Inglewood, California, on June 20, 1942. He spent most of his childhood in Hawthorne, California, a suburb of Los Angeles. He had two younger brothers, Dennis and Carl, who were also interested in rock and roll; all three could sing, and Brian could also play piano by ear. Their father Murry, a composer, became their first manager and used his music-business contacts to get them heard by labels.

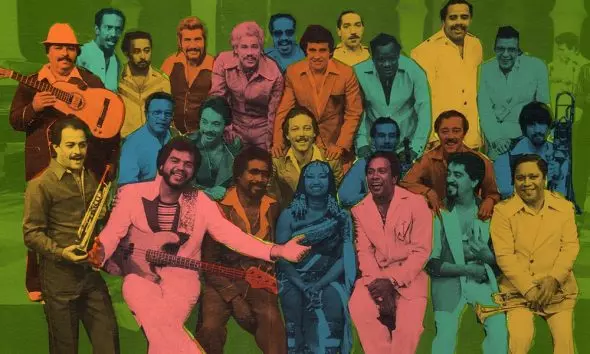

Wilson and his brothers formed the Beach Boys in 1961 with their cousin Mike Love and family friend Al Jardine. Their roles in the band locked in place early: Wilson sang lead on the records, played bass, and composed and produced the songs; Love sang leads and was the group’s frontman in concerts; Carl Wilson handled lead guitar; Jardine played rhythm guitar; Dennis Wilson played drums. All contributed to the group’s close harmonies, heavily influenced by the barbershop quartet the Four Freshmen and 1950s doo-wop; Love handled the bottom end, with Brian or Carl typically taking the top with their falsettos.

The Beach Boys’ first record, “Surfin’,” released on an independent label, reached Number 72 on the Billboard Hot 100; it joined a surfeit of trendy singles celebrating the waves by instrumental acts like the Ventures and the Marketts and the vocal duo Jan and Dean. (Wilson collaborated with the latter group, co-writing their Number One hit “Surf City” in 1964.) The modest success of “Surfin’” led the group to a deal with Capitol Records while the younger Wilson brothers were still in high school. Soon came a slew of joyous surf- and high school-themed hits, including three Top Tens in 1963 – “Surfin’ USA,” “Surfer Girl,” and “Be True to Your School” – as well as many more hits over the next few years, including the classics “I Get Around,” “Help Me, Rhonda,” and “Dance, Dance, Dance.”

Click to load video

But success came at a price. Brian, Dennis, and Carl frequently argued with their father, sometimes in front of Capitol executives, and the band fired him as their manager in early 1964. That December, Wilson, who was anxious about life on the road, suffered a nervous breakdown while flying to a show in Houston. He stopped touring with the group, with L.A. musician Bruce Johnston substituting for him on tour. Wilson turned entirely to writing and producing recordings for the Beach Boys, who would harmonize over the finished tracks once they returned from the road.

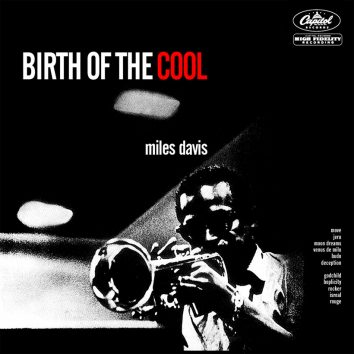

Freed from the touring life, Brian kept a close ear to his competition; he was particularly taken with the producer Phil Spector’s famous “Wall of Sound” style and wrote “Don’t Worry, Baby,” the Beach Boys’ swooning hot-rod ballad from 1964, in response to Spector’s work on the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby.” The Beatles activated his competitive streak, too, after he heard their 1965 album Rubber Soul. “When we were listening to it that night, I said to myself, ‘Now I’m gonna make an album just as good as Rubber Soul,’” Wilson recalled later.

He reached his goal – and, many would say, exceeded it – with Pet Sounds in 1966. The Beach Boys’ 11th album was a loose song cycle chronicling a romantic relationship from its giddy beginnings (“Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” a U.S. Top 10 hit) to its downhearted denouement (“Caroline, No,” issued as a Brian Wilson solo single). Pet Sounds was more floridly arranged than any rock LP of that time, and more introspective lyrically. The latter, especially, reversed course from the usual fun- and sun-centric Beach Boys. Wilson had his own ideas: “I thought of it as chapel rock,” he said later of the record. “Commercial choir music. I wanted to make an album that would stand up in 10 years.”

Click to load video

Pet Sounds performed modestly commercially, reaching Number Two in the UK charts but Number 12 in America – but it floored Wilson’s rock peers. Eric Clapton told Melody Maker, “I consider it to be one of the greatest pop LPs to ever be released.” Paul McCartney would say later, “I figure no one is educated musically ’til they’ve heard that album…It may be going overboard to say it’s the classic of the century, but to me, it certainly is a total classic record that is unbeatable in many ways…I’ve often played Pet Sounds and cried.”

Off the road, Wilson married his first wife, Marilyn Rovell, in 1964. (They divorced in 1979.) Their two daughters, Carnie and Wendy, would later go onto pop stardom as part of the adult-contemporary trio Wilson Phillips. Later, as a duo called the Wilsons, Carnie and Wendy made a 1997 album that featured two songs co-produced by their father.

After the mixed American sales of Pet Sounds, Wilson wrote and recorded “Good Vibrations,” at the time the most expensive single ever made, estimated to cost between $50,000 and $75,000. In the studio, he burned up 90 hours of tape to capture his exacting vision for the three-minute song. “It took six weeks to record,” Wilson told Uncut. “We recorded it in five different studios and I wrote out each player’s part on music paper.”

The result was the Beach Boys’ biggest record; the vivid, squealing Theremin-esque sound was as catchy as the chorus, and the record’s piece-by-piece construction, edited together from all those sessions, was cutting-edge studio trickery on par with the Beatles. This was pop on the brink of psychedelia, and Brian’s crowning achievement as a composer and studio mastermind. But Wilson was also credited for it so singularly, it deepened friction among the Beach Boys; as fawning articles on him amassed, his bandmates grew outwardly resentful. Carl Wilson told Melody Maker in 1966, “No, we are not just Brian’s puppets.”

Click to load video

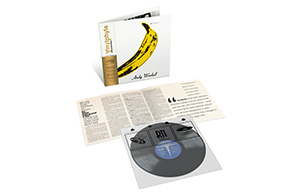

Wilson quickly set about trying to outdo himself and his peers yet again. In early 1967, he began work on the Beach Boys’ next album, Smile, a record he told friends would be a “teenage symphony to God.” He began recording short fragments of music, with a wide range of instruments and musicians, intending to edit the parts into a cohesive LP. He also brought in Van Dyke Parks, a fellow Capitol Records singer-songwriter, to contribute lyrics; they proved as dense and eccentric as the orchestrations (such as a refrain of “Columnated ruins domino,” from the standout track “Surf’s Up”).

But Wilson grew exhausted trying to construct his opus by editing miles of tape, and he found himself unable to cohere the many elements he’d recorded into a finished work. Parks departed the project, later saying, “I walked away from that funhouse.” On the brink of exhaustion, Wilson finally shelved the album. The Beach Boys re-recorded parts of it, along with other new material, and released the results in September 1967 as Smiley Smile; Carl Wilson called it “a bunt instead of a grand slam.” The Beach Boys’ decision not to play the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 also put them on the wrong side of cultural relevance. In the face of harder guitar rock from Jimi Hendrix and Cream, and more experimental hits from the Beatles and Rolling Stones, the Beach Boys were suddenly seen as passé. Their father Murry’s sale of Wilson’s publishing catalog for a mere $75,000 –containing many songs that have become as timeless as summer itself – didn’t help matters within the band.

Wilson wrote and produced songs on each of the Beach Boys’ post-Pet Sounds albums; some were taken from the aborted Smile sessions, particularly “Surf’s Up,” which became the title song of the Beach Boys’ 1971 album. But he retreated from public view; in interviews, the other Beach Boys would say, vaguely, that he was doing well. The reality was sadder: He was bedridden and burned out. He’d also been diagnosed as both manic-depressive and paranoid schizophrenic.

Click to load video

For the rest of the Beach Boys, the early 1970s began a shift. Under new management, they revived commercially as a touring act, sharing bills with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and the Grateful Dead. In 1974, their compilation album Endless Summer, heavy with the Wilson-led ‘60s hits, became a bestseller. Out on the road and in record stores, Wilson’s music was more beloved than ever.

In 1975, after years of attempts from Wilson’s friends and bandmates to get him back into the world, he began treatment with the celebrity psychologist Dr. Eugene Landy, who set him on an intensive, round-the-clock regimen of medication, behavioral coaching, and surveillance. For a while, this live-in therapy seemed to yield results. Landy ended treatment after one year, and Wilson’s management launched his return to the public eye. He was listed as the sole producer of 15 Big Ones in 1976, and wrote or co-wrote five of its songs; it was heavy on cover versions and underperformed commercially. But the critically lauded 1977 follow-up, The Beach Boys Love You, was entirely composed by Wilson, and totally weird. “Johnny Carson,” a catchy ode to the late-night talk-show host, brims with bittersweet insight into the travails of showbiz: “The way he’s kept it up could make you cry!” Brian also began playing with the band in concert again.

Click to load video

In 1982, Wilson overdosed and returned to intensive therapy with Eugene Landy. For the rest of the 1980s, Landy cultivated an invasive relationship with his famous client, including receiving co-writing and executive production credit on Wilson’s self-titled, critically acclaimed solo debut album in 1988. The Beach Boys sued Landy twice: in 1989, charging gross negligence, and in 1990, contesting Wilson’s will, which the group alleged had been changed at Landy’s insistence to benefit him with 70 percent of Wilson’s estate. Landy was ordered by a California court to separate himself from Wilson in 1991.

Wilson began to return to the public eye more frequently in the 1990s. In 1995, he was the subject of a documentary about his life, Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times. Directed by the record producer Don Was, it included interviews with him and testimonials to his genius by David Crosby, Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore, and many other artists. The same year, he reunited with Van Dyke Parks for Orange Crate Art, the first album credited to both; this time, Parks wrote the songs and Wilson sang them. In 1999, Wilson took an even more decisive step: he hit the road for the first time as a solo artist, backed by the L.A. power-pop group the Wondermints. The shows were received rapturously, and Wilson would remain a top live draw for years to come.

Smile remained unrealized during the 1990s, but in that decade, advances in recording technology caught up to Brian’s imagination: Instead of editing tape, producers used digital workstations like ProTools. With the assistance of his bandleader Darian Sahanaja, a lifelong Beach Boys fan, Wilson began putting together a finished version of Smile – and, to Sahanaja’s amazement, filled in missing portions on the spot. Once, Wilson “grabbed the lyric sheet out of my hands and started to sing the melody for what was to become ‘Roll Plymouth Rock,’” Sahanaja said. “It was so immediate that I couldn’t help but feel that it was always there.”

Click to load video

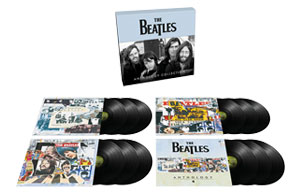

Wilson returned on the road to perform his complete version of Smile, and in 2004, he released it as an album, titled Brian Wilson Presents SMiLE. The first official version of the long-mythologized opus earned critical raves, placing second in the Village Voice’s critics’ poll that year, and reached Number 13 on the Billboard 200, selling 300,000 copies in the U.S. In 2011, Capitol finally released The Smile Sessions, a five-CD, two 7-inch box set full of long-bootlegged pieces of the puzzle. Seven more Wilson solo albums followed through 2021, and in 2016 he issued a memoir, I Am Brian Wilson, co-written by Ben Greenman. The same year, Wilson embarked on a tour commemorating the 50th anniversary of Pet Sounds.

In 2014 Wilson’s life story and relationship with his second wife, Melinda, was depicted by director Bill Pohlad in Love & Mercy, with the 1960s version portrayed by Paul Dano and the 1980s version by John Cusack. The film did very well with both film critics and its subject: “He loved it,” Dano said. “And Brian, he’s a little unfiltered, so you would know if he didn’t.”

In 2006, Bob Dylan offered him perhaps the ultimate accolade, telling an interviewer that Wilson “made all his records with four tracks, but you couldn’t make his records if you had a hundred tracks today.”