Night Fever: How Disco Brought Salvation To The Dancefloor

Disco was the music of liberation, inclusiveness, and empowerment with a four-on-the-floor bassline as its rallying cry.

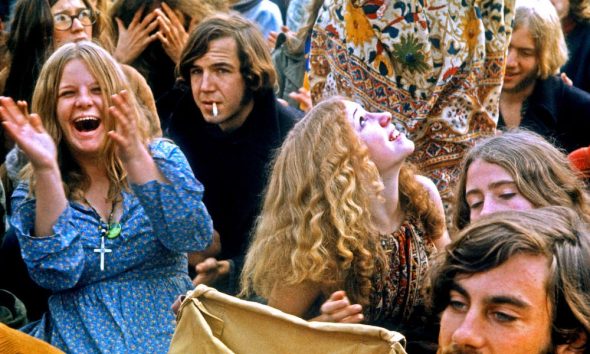

In many of its manifestations, dance music has often been derided and dismissed, from “disco sucks” to “heck no to techno,” but few genres have been so genuinely maligned as disco. During its height, it pervaded every aspect of pop culture, from music, fashion and lunchboxes to a point of doomed overexposure. While some wrote it off as a product of the hype machine run rampant by the industry, disco would have flourished without the label mechanics.

To one camp it was all empty glitz and glamour, smoke and mirror balls, and the pinnacle of 70s exhibitionism, but its origins were far grittier than the slick veneer of Studio 54. Before suburban moms were doing the YMCA at weddings, disco was the beating heart of the New York City underground. It was the music of liberation, inclusiveness, and empowerment with a four-on-the-floor bassline as its rallying cry.

If Motown had perfected the throbbing heartbeat that characterized the 60s, then the hi-hat disco stomp beat is what kick-started disco in the 70s and led to percussive psychedelia that ensnared a nation and its dancefloors. But how did disco go from Bianca Jagger riding atop a gleaming white horse to a literal inferno?

Listen to our Disco Fever playlist on Spotify.

Out from the underground

Disco didn’t get dropped on our doorsteps overnight, it took a perfect storm of elements to emerge from the decimated landscape of 70s New York. While the major metropolises had their own club scenes in the 60s, the twist and go-go crazes of the decade paled in comparison to the liberated debauchery that emerged out of New York’s underground. In order for dance music to thrive, you need venues to dance in, and many of the early disco clubs were created out of necessity. At a time when gay bars and sam- sex dancing were illegal in New York in 1969, pioneering DJ David Mancuso paved the way for underground disco parties with his private gatherings held at his loft in the Noho neighborhood of Manhattan.

Since his inaugural Valentine’s Day Party in 1970, “Love Saves The Day,” Mancuso has become enshrined in the firmament of nightlife history, creating a lifeline to underground gay culture and effectively setting the template for all the clubs that sprung up in the city’s forgotten spaces – Tenth Floor, 12 West, Xenon, Infinity, Flamingo, Paradise Garage, Le Jardin and Sanctuary. During this time the Stonewall uprising gave way to repealing New York’s draconian dance laws and the gay liberation movement became the driving force behind disco’s takeover of nightlife culture. The onslaught of disco openings continued in 1971 and beyond; soon came Haven in the Village, Machine in the Empire Hotel, the Ice Palace and the Sandpiper on Fire Island, the Continental Baths, Tamburlaine, and the storied Limelight.

The first disco record

In addition to creating the blueprint of disco clubs, Mancuso is also responsible for breaking essentially the first disco record with his discovery of African saxophonist Manu Dibango’s African-beat “Soul Makossa” in the spring of 1973. Mixing global beats with American R&B, it hit No.35 on Billboard‘s Hot 100 and became the first dancefloor hit popularized by a nightclub rather than a radio DJ. This would mark a tidal shift in the way hits were made, shifting the sphere of influence from radio DJs to club DJs. After taking the clubs by storm, DJs broke other uptempo soul hits that would tap into the mainstream and form the sonic foundation of disco, including “Rock The Boat” by Hues Corporation in 1973, Harold Melvin And The Blue Notes’ “The Love I Lost,” “Dance Master” by Willie Henderson & The Soul Explosions the same year, then George McCrae’s “Rock Your Baby” and “Main Line” by Ashford & Simpson in 1974, respectively.

One of the key players who was crucial to developing the disco sound was drummer Earl Young. As the founder and leader of The Trammps and one third of the Baker-Harris-Young rhythm section that included bassist Ron Baker and guitarist Norman Harris, Young played with everyone from The Intruders, the O’Jays, The Three Degrees and was part of the 30-piece house band called MFSB for Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff’s Philadelphia International Records label at the famed Sigma Sound Studios.

The disco groove was born

It was there he would make music history, speeding up the former ballad “The Love I Lost” and adding the hi-hat pattern on the spot. And thus, the “disco groove” was born. You can’t unring the disco bell and once this galloping rhythm started there was no stopping it. In 1973, MFSB would release “The Sound of Philadelphia” better known as “TSOP’ for the theme for Soul Train, featuring a sweeping instrumental section, a steady beat, and sexy backing vocals by the Three Degrees that would becoming the winning formula for disco.

An equally influential instrumental piece was “Love Theme” by Barry White‘s Love Unlimited Orchestra. With its sexy wah-wah guitar, it became one of few orchestral singles to reach No.1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, further incorporating the orchestral sound and extended running length into future disco.

A producer-driven medium

From its early incarnations to the later hits, disco remained a producer-driven medium. Just it the genre birthed influential DJs it also gave rise to the super-producer: from Rinder & Lewis in Los Angeles to Baker Harris & Young in Philadelphia, Ashford & Simpson in New York, and Van McCoy, the disco hitmaker and man behind the “The Hustle.” While production shaped the sound, the genre also served as a springboard for emerging soul singers and strong vocalists of all stripes including Gloria Gaynor.

Before she officially voiced the anthem of the gay movement with “I Will Survive’ in 1978, Gaynor’s cover of the Jackson 5’s “Never Can Say Goodbye” for her MGM debut EP became the first No.1 song on Billboard‘s first dance chart upon its debut in October 1974, and the EP featured the first-ever “disco mix” by Tom Moulton, a DJ and studio innovator who beat-mixed the singles “Honey Bee,” “Never Can Say Goodbye” and “Reach Out, I’ll Be There” into one continuous disco medley on one side of the vinyl.

In the annals of dance music history, Tom Moulton may have a leg up on all of the legendary DJs of the day as the originator of the remix and 12” single. Another invention by necessity, Moulton created a continuous mix on reel-to-reel tape to keep people from leaving the dancefloor during song breaks. In early 1974, he continued his experimentations by elongating pop songs beyond their standard three-minute mark.

By stripping the songs down to just their raw percussive state, he birthed the “disco break,” beloved by dancers for the driving tribal quality and by DJs as a tool to mix with. His other invention, the 12” single, was merely a happy accident. After running out of 7” blank acetates to cut a reference disc, he ended up putting a song onto a 12” blank instead – spreading the groove out, raising the levels and creating the standard format of dance music for the next three decades.

Soon Moulton was a hot commodity for working his mojo on OK singles and turning them into hits. His signature is all over songs like Don Downing’s “Dreamworld,” BT Express’ “Do It (’Til You’re Satisfied),” The Trammps’ “Disco Inferno,” The People’s Choice’s “Do It Any Way You Wanna” and Andrea True’s “More, More, More.” He would also become an official chronicler of New York’s disco scene, writing Billboard’s first dance column, Disco Mix and would go on to produce Grace Jones‘ first three albums.

As labels quickly realized that DJs were the gatekeepers of the disco-consuming public, these nightclubs became more than just the settings of lost weekends and instead were treated as research and development labs to test songs out for mass consumption. Hit records would come and go, but the DJs were the real stars of the show, each with their own style and dancefloor to lord over, with David Mancuso at the Loft, Francis Grasso at Sanctuary, Tom Savarese at 12 West, David Todd at Fire Island’s Ice Palace, Bobby Guttadaro at Le Jardin, Nicky Siano at Gallery, Tee Scott at Better Days, Richie Kaczor at Studio 54 and last but certainly not least, Larry Levan at the Paradise Garage.

The rise of the DJ

Previously, a diverse set of individual records would make up a DJ set but Francis Grasso changed all that by innovating the practice of beat-matching aka mixing or blending. He along with the DJs of the day would take dancers on an audible journey, building them up to a cathartic release of sweaty euphoria. No longer were DJs considered the backdrop of the club but now they were the main attraction with Larry Levan’s legendary Saturday night sets or “Saturday Mass” drawing hundreds of revelers to an old parking garage in dingy Soho.

While Studio 54 represented the uptown glitz and glamour of the moneyed and famous, Paradise Garage was a utopia for black, Latino, and LGBTQ New Yorkers answering the siren call of Levan’s genre-blending mix of disco, soul, funk, R&B, new wave, and an emerging strain of music that would later be known as house music. Since the Garage opened in 1977, Levan expanded into music production and championed many tracks, including Peech Boys’ “Don’t Make Me Wait” and Loose Joints’ “Is It All Over My Face” and turned many soul singers like Taana Gardner and Gwen Guthrie into disco divas through inventive mixing.

The queens of disco

Before Gardner and Guthrie, there was the Queen Of Disco, Donna Summer, and her seminal recording with German synth-master Giorgio Moroder, “Love To Love You Baby.” This was Moroder’s answer to Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin’s seductive masterpiece, “Je T’aime… Moi Non Plus,” with Summer channeling a breathy Marilyn Monroe for 16 minutes and 40 seconds of ohhs and ahhs. While orchestral accompaniment had been the bedrock of disco, Moroder changed the game with an entirely synthesized background and the duo would pair up again for “I Feel Love” in 1977 and ‘Last Dance’ in 1978 on Casablanca Records.

Casablanca became one of the primary purveyors of disco. As one of the first major labels to embrace the genre, it broke acts like George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic and The Village People. Throughout the decade, other labels were instrumental in bringing the underground sound to the masses, including Salsoul, West End, Emergency, Prelude Records, MCA, TK Records, Island, Polydor, and 20th Century.

When disco went airborne

By 1976, disco had gone airborne, with over 10,000 discos in the US alone, including inside roller rinks, shopping malls, and hotels. That same year, five out of 10 singles on Billboard’s weekly charts were disco, and one year later it reached its cultural apex with the release of the film Saturday Night Fever. Even before the film’s release, the Bee Gees had hits with “Stayin Alive” and “How Deep Is Your Love” when they were asked to contribute songs to the film’s soundtrack which also included “Jive Talkin” and “You Should Be Dancing.”

The soundtrack sold a staggering 25 million copies, topped the US charts for 24 weeks, and for the first time in film history, the soundtrack sold the movie. In addition to making John Travolta and the Bee Gees household names, the soundtrack also introduced the mainstream to more urban disco hits like the Trammps’ “Disco Inferno” and Kool & The Gang’s “Open Sesame.” The film had officially opened the floodgates and, unsurprisingly, everyone was riding the disco wave, from Rod Stewart’s “Do You Think I’m Sexy” to The Rolling Stones’ groove-heavy “Miss You,” Blondie’s “Heart Of Glass,” and Diana Ross got Chic-ified with “I’m Coming Out.”

From domination to demolition

As disco continued to steamroll the airwaves, forcing funk and rock off pop radio, a backlash was inevitable and culminated in the infamous Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park in Chicago on July 12, 1979. It all started with a disgruntled radio DJ named Steve Dahl who lost his job after his station went to an all-disco format. Thanks to dwindling ticket sales, he convinced White Sox promoters to offer game admission for less than $1 if fans brought disco records to burn. But Dhal’s “disco sucks” rallying cry represented more than just an aversion to dance music.

After all, it wasn’t just disco records that went up in flames that day, but music made by black artists like Tyrone Davis, Curtis Mayfield, and Otis Clay. As rock was being elbowed off the radio by artists of color and gay performers like Sylvester and the AIDS crisis was just beginning, the disco bonfire was a kind of moral panic on behalf of straight, white, and male America. Disco’s backlash underscored just how subversive the music was. But disco didn’t die that day. It penetrated pop music throughout the 80s and went underground in, ironically, Chicago, only to be reborn several years later as house music.

Looking for more? Discover Night Fever: Bee Gees And The Birth Of Disco.

Vaughn Maurice Buel

April 23, 2017 at 2:05 am

Love, love, love Disco!!!

Stuffed Animal

May 20, 2019 at 5:40 pm

Disco, with its roots extending into Black Gospel, Latin music, classical music, Indian music and beyond, was an early expression of ethnic diversity. Ultimately, people were not ready for it and reacted against it. But for a sound that non-Disco performers berated as “not really music”, Disco has produced an amazing number of enduring Pop standards, among them “We Are Family”, “Turn The Beat Around”, “Rock The Boat”, “Lady Marmalade”, “Dancing Queen” (Disco that actually pre-dates the Disco era), “I Will Survive”, “Funkytown”, just about anything by KC and The Sunshine Band and the enormously influential “Good Times” by Nile Rodgers and Chic. I miss Disco’s high vocal standards and equal emphasis on melody and rhythm. Good singing and strong melodies are sorely missing from today’s music!