Rudy Van Gelder: The Man That Made Jazz Sound So Hip

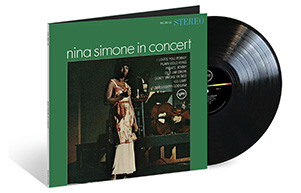

It was Rudy Van Gelder’s brilliant engineering skills that give so many jazz recordings, in particular those for Blue Note Records, their distinctive sound.

Today we celebrate the man that made jazz sound so hip, Rudy Van Gelder, who was born on November 2, 1924, and later passed away in his home, which doubled as his studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, on August 25, 2016, at the age of 91.

It was Rudy Van Gelder’s brilliant engineering skills that give so many jazz recordings, in particular those for Blue Note Records, their distinctive sound. But Van Gelder did not solely work for Blue Note. He was an engineer for hire and his work for Prestige on Miles Davis’s 1950’s sessions produced some of his finest work, as it did on John Coltrane recordings for the same label; later he made some wonderful records for the impulse! label.

Listen to the best of Blue Note on Apple Music and Spotify.

Van Gelder’s first session for Blue Note was in January 1953 with saxophonist and composer Gil Melle, who has the distinction of bringing Van Gelder to Alfred Lion’s attention. These very early sessions for Blue Note and other independent labels sound so wonderful, despite the fact that Van Gelder’s studio was in the living room of his parent’s house.

Making history in the living room

According to Blue Note producer, Michael Cuscuna, the concept of a studio in Van Gelder’s parent’s living room was not as outrageous as it sounds: “They were building a new house. Rudy had been doing some recording with a makeshift set-up, and he said he really wanted to build a recording studio. So, in the living room, they built all kinds of alcoves, nooks, and little archways that they designed because Rudy had ideas for them acoustically. At the end of the living room, he built a control room with soundproof glass. So it was professional.”

The Hackensack living-room studio of Rudy Van Gelder gave so many a distinctive sound, the kind that makes you feel as if it was recorded just a few minutes before you hear it, almost as though it is in the room next door. As Van Gelder commented many years later, “All I can tell you is that when I achieved what I thought the musicians were trying to do, the sound sort of bloomed. When it’s right, everything is beautiful.”

“Rudy’s a very knowledgeable and soulful person. He’s not like some – they call them ‘needle noses’ – they just look at the needle on the meter.” – Alfred Lion.

In July 1959, there was a significant change when a new state-of-the-art studio in nearby Englewood Cliffs replaced Rudy Van Gelder’s “living-room” studio in Prospect Avenue, Hackensack. Van Gelder had outgrown the old space and in 1957 had begun planning for a new one. He took inspiration from the work of architect Frank Lloyd Wright, whose designs and large-scale models he and his wife had admired at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Wright and a group of architects had come up with the concept of Usonian houses – beautiful yet affordable homes built from inexpensive materials in his trademark organic style. A member of the Usonia group, David Henken had built some houses in nearby Mount Pleasant. He met Van Gelder and they soon began talking about building a home and studio at a price Van Gelder could afford.

One can get a feeling akin to religion

By the end of 1958, and with plans drawn up, through Henken, Van Gelder found a builder who took on much of the carpentry for the project, including the 39-foot-high, beamed studio roof. This cathedral-like structure was built in Portland Oregon then shipped to New Jersey where a 90-foot crane lowered it into place.

Ira Gitler describes the new studio in his liner notes to the Prestige album The Space Book by Booker Ervin: “In the high-domed, wooden-beamed, brick-tiled, spare modernity of Rudy Van Gelder’s studio, one can get a feeling akin to religion; a non-sectarian, non-organized religion temple of music in which the sound and the spirit can seemingly soar unimpeded.” In fact, the tiles weren’t brick at all, but cinder blocks impregnated with tan coloring.

Rudolph Van Gelder was born in Jersey City on November 2, 1924. His parents, Louis Van Gelder and the former Sarah Cohen, ran a women’s clothing store in Passaic, New Jersey. Rudy became interested in jazz at an early age, playing trumpet, and by his own admission, badly, but it was technology that fascinated him, with an early interest in Ham radio.

He went to the Pennsylvania College of Optometry in Philadelphia to study optometry and for more than a decade, he was an optometrist by day and a recording engineer when time allowed. His increasing success allowed him to follow his first love full time by the late 1950s.

Working with the greats

Rudy Van Gelder was married twice; both marriages ended with his wives’ deaths. He was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master in 2009 and received lifetime achievement awards from the Recording Academy in 2012 and the Audio Engineering Society in 2013. When he learned that he would be honored by the N.E.A. at a ceremony in New York, Mr. Van Gelder said in a statement, “I thought of all the great jazz musicians I’ve recorded through the years, how lucky I’ve been that the producers I worked with had enough faith in me to bring those musicians to me to record.”

There is hardly a jazz artist who did not benefit from Van Gelder’s skills, whether it was guitarists like Wes Montgomery, Grant Green or Kenny Burrell, or pianists such as Bill Evans, Horace Silver, and Herbie Hancock, or artists as diverse as Eric Dolphy, Jimmy Smith, Cannonball Adderley, and Chet Baker, every one of them owes him for making their music sound just that little bit more special.

The sound that Rudy Van Gelder achieved on all his recordings is as hip as it is possible to get. With his knack for placing you in the room with the musicians, he has defined what we think of as great jazz recordings. While there was technology involved, the buildings themselves, great musicians to work with, and producers like Alfred Lion who knew what they were trying to achieve, it is Van Gelder who supplied some indefinable ingredient that helped make magic.

Looking for more? Discover the 10 Essential Blue Note Albums You Need To Hear.

Judith Alvarez

November 3, 2014 at 1:24 am

Great music!!

Donald Lewis

November 3, 2014 at 6:00 am

Thanks for the intro.Looking forward to some great jazz news.

Anthony

November 3, 2014 at 8:33 pm

Insightful and special. Really good to know the history of recording this great music.

f.a.k. lateef-adeleye

November 8, 2014 at 7:14 pm

marvellous music. you can’t go wrong with good jazz. i enjoyed it immensely.

Bertrand Leblanc

November 24, 2014 at 11:08 pm

I just listen to a song by the great Bill Evans, and could not figure out how in 1965, you were getting this type sound on a live performance, I would like to thank you for sharing your history of recording industry at the time, I only assume that the only one who could afford this this type of equipment would Capitol records in L.A. or George Martin. again thank you.

Eric Pulsifer

May 25, 2015 at 8:31 am

He was the engineer on almost all of John Coltrane’s Prestige recordings, wasn’t he? I know some great sounds came out of that house.

Jim Burlong

November 2, 2015 at 6:05 pm

Rudy Van G, What a fantastic contribution to jazz and a time line to all of us jazz heads. The Master of The Blue Note sound.

Ben d'Abo

August 26, 2016 at 5:23 pm

Also the recordings for Creed Taylor’s CTI Records , which I want to do a documentary about

Robert Moehle

November 2, 2017 at 7:25 am

I suspect one of the main ingredients of Rudy Van Gelder’s sound was “leave it alone!” An acoustically neutral room, really good condenser mics, clean wide-range preamps, and tape. I think that is it.

Julian Vein

March 22, 2021 at 3:56 pm

RUDY VAN GELDER – A CRITIQUE

I’m not technically minded in matters of recording techniques, so bear with me if I sometimes use inappropriate technical terms, but I’m going on what my ears tell me. Most of the criticism refers to his Blue Note work and, as noted, much of his work is fine. If one does an internet search it is most unlikely you will come across much criticism of his work. Maybe this was because his critics preferred to remain silent because of the overwhelming praise he was receiving from listeners and musicians alike?

“He’s a good engineer, but he can’t record pianos”

“You can’t hear the bass”

“You can’t hear the drums”

“He uses arbitrary reverb”

“He uses microphone rather than studio ambience”

“Frontline instruments appear to be overlaid over background ones”

“[Van Gelder’s] customary one-dimensional balancing of the instruments”

These are some of the criticisms I’ve heard levelled against RVG over the years, yet most collectors, record producers and musicians who were recorded by him appear to be in awe of his efforts. Incidentally,

Van Gelder seems to have come to our attention for his work on the famous Miles Davis Prestige session of Christmas Eve 1954, which included Thelonious Monk and Milt Jackson. When I played this session to my brother (an electronics engineer) many years ago, his comment was “There’s a lot of knob-twiddling going on”, which there was, although I hadn’t given it much attention before. Apparently, this was the first use of a mixing console—I remain to be corrected on this—but RVG seems to have gotten carried away by his own cleverness, and resorted to excessive gain-riding, which resulted in the music fading in and out, although this had nothing to do with the overall sound. I have never seen this aspect of that recording mentioned in any review. Did RVG not bother to make some test recordings before making a commercial one? Previous Prestige recordings by him were with “normal” ambience.

His theory of recording seems to be the need to produce a “neutral” sound rather than the natural ambience of his studio, so that you are meant to get the sound of a band playing in your room, rather than reproducing the sound of his studio. However, when I listen to many of his efforts I get the feeling of a self-consciously produced, artificial sound. For instance, drums don’t sound distant, they often sound “small” and recessed, giving a “ricky-ticky” effect. What you get is the effect of there being no ambience until an instrument is actually being played. Some of his work contains distortion, especially the piano sound, but that may be the result of remastering onto CD, although some of that was his own work. It may, of course, be the quality of the piano in his studio. Usually, there is often a lack of “airiness” in his sound, which one can hear on other engineers’ less technical work. Was this a result of over-miking? Sometimes there is a lack of texture in the instrumental tones, as if he’s “defuzzed the peach”. I recently played my CD copy of Archie Shepp’s “Kwanza” on Impulse!, and although the music wasn’t to my taste, I did notice that the ambience of the music was natural, and you could hear the textures of the ensembles clearly. Most of Shepp’s Impulse! recordings were done by RVG, and had the usual sound strictures, making them something of an effort to listen to, unlike “Kwanza”. On this session the ensemble instrumental timbres seem to mesh together, whereas on a RVG recording all the instrument they sound separate.

Also, the dynamic range on RVG recordings seem less than it should be, and the music fails to “fill” the speakers even with the volume turned up. Another problem is the changing balance from behind one soloist to another, although other engineers were guilty of this. However, describing him as the “least bad” is not much of a compliment!

His recording technique philosophy seems to go back to a Gil Mellé, a privately recorded session, subsequently sold to Blue Note. Alfred Lion was impressed with it and asked RVG to reproduce it for further Blue Note sessions.

Why can’t you hear the bass properly? Possibly, RVG figured, you can’t hear it properly in a real playing situation anyway. Perhaps he eschewed the “West Coast” approach of recording the bass crisply because that wasn’t how one heard it in live circumstances, and perhaps that a well-recorded bass line is a distraction from the rest of the music? For what it’s worth you can hear the bass clearly enough in solo, and in slow performances—on faster numbers it seems as if the bass notes decay before RVG can capture them fully. I don’t know if the musicians in his studio could hear the bass lines clearly or not. If the famous Francis Wolff pictures of the sessions are anything to go by, the musicians weren’t using headphones, and were hearing the bass sound as it came to them direct. Apparently, RVG moved the microphones when photographs were being taken, so we have to speculate on what the recording setup was.

However, he is inconsistent—some of his efforts are quite pleasant to listen to, e.g. the Prestige Swingville sessions, and even some Blue Notes. His Prestige recordings are usually more natural-sounding than the Blue Notes. His live recordings are a different matter—the natural ambience can be heard here, presumably because he is unable to manipulate the sound to his taste in an unfamiliar environment.

Some of his later work was quite poor, even by his standards. Take, for instance, the Blue Note recordings of Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry of the mid-60’s. They’re thin and stringy, totally lacking in guts. I actually commented on this in a letter to the Melody Maker at the time. Was this a change in equipment or recording philosophy? Or even tape?

Of course, if the music is outstanding, then one can ignore the inadequacies of recording to some extent. If the music is average then one’s mind tends to wander to the recording quality. It almost as if Alfred Lion was afraid of music that might “frighten the horses”!

I have very few Blue Note originals: Sonny Rollins, Leo Parker and Dizzy Reece—not typical Blue Note fare, and RVG seems to have a different recording philosophy for them.

In the end I often find listening to a RVG recording something of an endurance test; even when it’s a good one I’m still listening out for problems! Listening to recorded music should be a relaxing affair, not a burdensome one!

I suspect there are many collectors like myself who possess more recordings by RVG than any other engineer, which leads to a sense of frustration! This doesn’t absolve some of his contemporary engineers (e.g. Columbia’s from the mid-50’s on, including Miles Davis’s “Kind Of Blue”), who had their own faults. Their faults appear to be the result of inadequacies in their understanding of what is required, whilst his appears to be the result of a carefully carried-out plan.

Julian Vein

Scott McDowell

March 29, 2021 at 4:56 am

I believe that Art Blakey said it best, “Some of you guys are so #@d$*#n clinical. You can’t define nor analyze a tonal conversation. Whether audibly or metacognitively. Its music…listen and enjoy.