‘Love In Us All’: A Pharoah Sanders Spiritual Jazz Classic

The record stands tall in a career full of spiritual jazz classics.

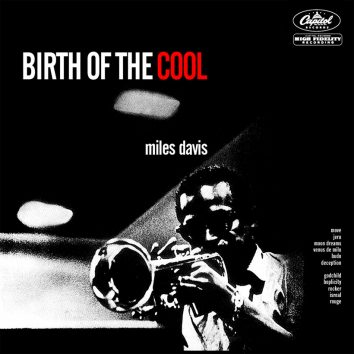

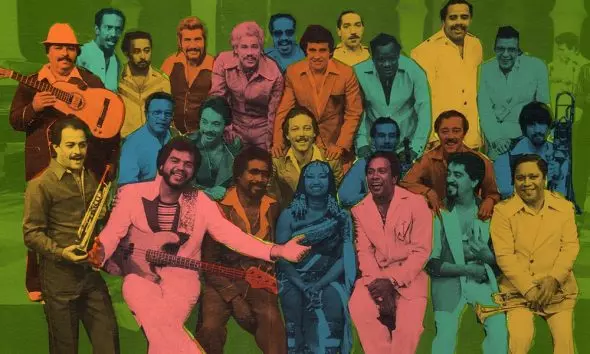

“Spiritual jazz” has been variously defined as modal, free, avant-garde, Pan African, and Afrofuturistic. Pharoah Sanders’s Impulse Records discography (1967-1974) might just as effectively suffice as a primer. Born and raised in Little Rock, Arkansas, Sanders escaped the South’s virulent racism for the Bay Area, playing tenor saxophone in blues combos, before eventually settling in New York City in the early ’60s. There, he found his voice amongst a cadre of exciting musicians (Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, Marion Brown, et al.) challenging the harmonic, rhythmic, and conceptual conventions of jazz, with an eye towards their common inspirational North Star, John Coltrane.

Sanders’s holistic approach to life, and distinctly expressive playing – at turns warm, intense with the tonal residue of his honky tonk past, or unleashed in percussive bursts like a Pentecostal sermon – would also find a fan in Coltrane himself. Joining the tenor giant’s post-classic-quartet group, he notably appeared on Ascension – Trane’s co-sign of jazz’s young radicals’ “New Thing” as his next step in the spiritual journey charted by A Love Supreme. Opposite his hero, Sanders was often framed as a fiercely free and disruptive foil. However, his emergence as a leader on his own recordings after Coltrane’s passing in 1967 revealed the true depth of his artistry. Seizing on simple melodic themes, he’d regularly expand these ideas into explorations of consciousness lasting entire album sides. The most transcendent of these – “The Creator Has a Master Plan,” “Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt,” “Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah,” “Let Us Go Into The House Of The Lord” amongst others – were blessed with the power to stir, ignite, and calm the soul, sometimes within the same breath.

Click to load video

Recorded in 1972 but released two years later, Love In Us All, is another essential addition to this canon. “Love Is Everywhere,” the first of its two 20-minute pieces, is a modal masterpiece. It commences – in the tradition of A Love Supreme’s “Acknowledgement” – with a repeated bass figure nimbly played by Cecil McBee. The rest of the band – Joe Bonner on piano, Norman Connors on drums, and the percussion triumvirate Badal Roy, James Mtume, and Lawrence Killian – builds around this main theme, gaining volume like a procession approaching. When Pharoah makes his entrance, he’s not playing reeds but singing the title refrain in a joyous call-and-response with the band. As markedly as it escalates, the music fades and disappears into the distance. Bonner’s solo piano quietly reintroduces the theme, Pharoah re-enters on soprano saxophone, sounding as lyrical as ever, and everyone else joins in in reflection. The initial euphoria is merely a prelude to a more meditative, broader celebration – as if to declare, love is only everywhere if it’s also sustained.

“To John” resumes the comforting tone through Pharoah’s introduction. But where “Love Is Everywhere’s” raucous B-section flirts with chaos only to pull itself back from the precipice, here the group fully embraces it, diving headlong into a full 10-minute-plus stretch of cathartic free blowing and thunderous, rolling piano and percussion. For the unprepared, it’s undoubtedly a challenging listen. Pharoah’s flurries of notes screech with pure emotion in dedication to Coltrane – embodying perhaps the anguish and despair of mourning, or the exaltation of a loving tribute, or a more complicated recognition of both. When his shrieks subside and the waves of bass, drums and percussion settle around Bonner’s piano, the tension break feels almost revelatory. Yet it’s simply a re-affirmation of what Sanders, who passed away in 2022 at age 81, always conveyed through his work: that there’s nothing quite like music’s power to heal.