From Haight-Ashbury To Sunset Strip – The Rise And Rise Of Classic Rock

Marty Balin opened the Matrix club in San Francisco on 13 August 1965 featuring his new band Jefferson Airplane. Over the next two years, Big Brother & the Holding Company, The War Locks, [future Grateful Dead] the Doors and many dozens of acts would play inside his room. Born Martyn Jerel Buchwald in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1942, Balin moved to the Bay area at age four; Balin’s father Joe Buchwald was a lithographer, and printed more than 200 different posters for music shows at the Matrix club, the Fillmore and Avalon ballrooms.

In 1962 Marty renamed himself Marty Balin and began recording with Challenge Records, at the legendary Western Recorders in Hollywood with the area’s top session players. ‘Nobody But You’ and ‘I Specialize in Love.’ He subsequently became lead singer of a folk music quartet called the Town Criers, followed by a brief stint with the Gateway Singers in 1965.

According to Balin, “I wanted to play with electric guitars and drums, but when I mentioned that notion in clubs that I played, the owners would say, ‘We wouldn’t have you play here. Not with drums and electricity. This is a folk club.’ So I decided to open my own club.” “Marty is the one who started the San Francisco scene,” said former Jefferson Airplane and Jefferson Starship manager, and Balin roommate, Bill Thompson.

“I think San Francisco was full of all these people who were talented and who were expressing themselves or their rights or playing music,” Balin told me in a 2015 interview. “And I think San Francisco has a lot to do with that. I don’t know if it’s the geomagnetic forces of the earth and the ocean but something went on there. It’s a lot different than the rest of the world.”

Two months after the release of their 1967 self-titled debut album, the Doors were booked for a 7 – 10 March stint at the Matrix. ‘Break on Through’ hadn’t cracked the top 50 on the charts. “The songs, mainly from the first two LP’s, had not come into focus live quite yet,” offered journalist Rob Hill, now editor of MG Magazine. “And Morrison-dresses in a rumpled brown V-neck sweater and slept in brown corduroy pants-had not found his stage voice or persona. This would come some 5 months later.”

“In San Francisco,” added Doors’ drummer, John Densmore, “first at the Avalon, and then Fillmore Auditorium, where we kinda scared everybody. I could tell they liked us, we were the underbelly. You forget in the Summer of Love there is the Vietnam War on everyone’s mind. San Francisco was quiet. They stared at us like we were from Mars. We knew that was making an impact.”

In 2016, as you lovingly gaze at your 1966-1970 Fillmore and Avalon reproduction posters, and marvel at the countless mind-blowing mixtures of circa ’67 live sounds happily discovered on CD reissues and the digital bins, streamed links, mostly from shows promoted by Bill Graham or Chet Helms at the Fillmore and Avalon Ballroom, do know there were other clubs and concert halls in California that bravely presented many of your fave rave bands during 1966-1970.

In 1976 I interviewed entrepreneur Bill Graham for Melody Maker at his home in Mill Valley, California. Also in attendance were Jerry Garcia and Carlos Santana. “There was never a San Francisco sound, or a Boston sound,” Graham explained. “They may do the same thing to an audience though, which is give them pleasure.

“There is something that they [Grateful Dead] always had in common from the beginning, something hardly spoken about in the media after all these years. The San Francisco bands, starting with the Dead, always went to the gigs with the intention of putting it out there. It was the lack of professionalism at the beginning that made that possible. It wasn’t that the contract said 45 minutes and ‘that’s what we’ve got to play.’ They were the first one who asked to play longer. They wanted to extend the relationship between the audience and themselves.”

“We in the scene in Europe knew all about San Francisco,” Donovan mentioned to author Jeff Tamarkin in his 2003 book, Got a Revolution! The Turbulent Flight of Jefferson Airplane. “I heard about the Airplane when I first came to California in 1965. I did not go to San Francisco until 1966, but for me, they were the band there at the time. I saw them from the start. I wrote the song ‘Fat Angel’ before I met them. The artists of the scene communicated through vibes.”

Over many years, I conducted a series of interviews with Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kantner. We talked at length about Bill Graham, the Fillmore, and travels with Jefferson Airplane.

“As far as San Francisco being suspect of L.A. and Hollywood people, we always tried to get above that if possible as a general rule,” Kantner stressed to me. “People didn’t like the Doors. ’Cause they were from L.A. [Laughs.] I rejected the suspicions of L.A. as a general rule. I thoroughly enjoyed L.A. and New York. I could make myself comfortable in either one of those cities. I liked San Francisco a lot and there was all that L.A. stuff versus San Francisco. It went on. I didn’t pay any attention to it. I enjoyed bands from both towns.

“Again, getting to the heart of the matter, the point is if you find something that makes you joyful, take note of it. Amplify it if you can. Tell other people about it. That’s what San Francisco was about. Both musically, idealistically, and metaphorically and every other way. That’s what we did here. We were in a place that encouraged and nourished that kind of thinking and still does to this day and we took full advantage of it. We weren’t up on soapboxes complaining like the Berkeley people. And we need those people too. Those people are very valuable but that’s not what we did.

“As for our sound,” revealed Kantner, “It’s not folk music. I don’t know what it is. It’s just we all took up and started in folk music and then branched out. Jefferson Airplane had the fortune or misfortune of discovering Fender Twin Reverb amps and LSD in the same week while in college. That’s a great step forward.”

“And San Francisco was very good, I think, particularly the musicians at transmitting the goodness of the day, rather than complaining about the badness of the day. The Fillmore and the Avalon. I went to the Human Be In. The summer before the Summer of Love I always mention. Everything was possible. And plausible, even. And we got away with it all. More or less. Mostly. You went to the park, the Fillmore, Monterey, to get absorbed in the whole whatever it was going on.

“In 1966, ’67, there was all sorts of music going on. That became that because of what we did in San Francisco and encouraged Bill Graham. He really had all those strange combinations of acts on the bill. We didn’t think of them as opening acts. We just thought of them as other acts that are really good. We encouraged Bill to book them.”

In February 1967, Otis Rush & His Chicago Blues Band, Grateful Dead and Canned Heat Blues Band, April that same year, The Chambers Brothers, Quicksilver Messenger Service and Sandy Bull, then in August, Muddy Waters, Buffalo Springfield and Richie Havens. On other nights there was Howlin’ Wolf, The Who, Blue Cheer, and even Count Basie and his orchestra – a veritable who’s who of popular (and happening) music.

According to Kantner, “The reason that people came to the Fillmore was not the band. People came to the Fillmore much like a Harvest festival. The same reason they came to the Human Be-In. To be there. And if there were good bands playing, that was an added plus. But not many people were coming as fans of the band. Not many. Some. That wasn’t the draw of the Fillmore and the Avalon.”

In a 2001 interview I did with Grace Slick, she commented about the Fillmore. “The audience and the bands were not that separate. In other words, a large amount of the audience was the other bands at the time. So it was casual, and not that separated. As a rock ’n’ roll force I mostly liked Bill’s energy. Both physical and mental. He was able to keep an awful lot of balls in the air.”

Long before he became an authority and scholar on Bob Marley and reggae music, poet and actor Roger Steffens was living in San Francisco, nurtured by the ‘60’s counterculture.

“On November 2, 1967, the night before I shipped out for Vietnam, three Army buddies and I drove out of the Oakland Army Terminal across the bridge to Winterland in San Francisco. It was to be the debut of a new English band, but we were there to see the opening act, Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company. I had grown up in the ’50s in New York City and had seen almost all the major figures of the era in Alan Freed’s big stage shows. But not since Jackie Wilson had I seen a performer of such soul-searing power as Janis that night. She was like an exposed nerve ending with a voice, and I felt totally drained emotionally after her startling set.

“Then Richie Havens appeared in the middle of the huge dance floor, alone on a stool with his acoustic guitar, encircled by a couple of thousand kids. He held us in the palm of his hands for the next hour, after which Bill Graham came out on stage looking very apologetic. “I know you all came here tonight and paid three dollars to see three acts, but Pink Floyd can’t get out of Customs in time.” So I went to the [local club] hungry I and got the current group there to fill in. “Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Ike and Tina Turner!”

“Janis raced out of the dressing room clutching a full bottle of Southern Comfort and worked her way to the foot of the stage, right beneath Tina, whooping and hollering encouragement all through Tina’s outlandish, heart-racing set, draining the bottle in the process.

In the south, in Los Angeles, The Whisky a Go Go in Hollywood opened at the start of 1964. “As early as ’65, “ writer Kirk Silsbee told me in 2015, “there were other headliners: Paul Butterfield, the Rascals, the Leaves, Love, the Mothers of Invention, the Beau Brummels, Otis Redding, the Gentrys; by the end of that year, Los Angeles magazine pronounced the club ‘the inviolable center of What’s Happening.’

“In the spring of ’66, at the urging of Byrds bassist Chris Hillman, owner Elmer Valentine installed Buffalo Springfield as the Whisky’s house band. It quickly established them as the next important milestone in the Hollywood Renaissance—after the flowering of the Byrds, Love and Doors.

“In December ’66, the KRLA Beat predicted: The Sunset Strip in Hollywood will die for teenagers and will go back to an over-21 hangout. As a result of the Pandora’s Box dustup that inspired ‘For What It’s Worth’ by Steve Stills, the city revoked the Whisky’s dance license. Valentine reacted by booking black headliners onto the mostly all-white Strip: the Miracles, the Temptations, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Martha and the Vandellas, the Four Tops, the Impressions, Bo Diddley, Hugh Masekela, jazz organist Jimmy Smith and Jackie Wilson.

“Near the end of 1967 the over-21 policy restriction had been relaxed to age 18. Sunset Strip soul dovetailed with locals Peanut Butter Conspiracy, the Gene Clark Group, Kaleidoscope, Sweetwater and a San Francisco jolt via Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, Moby Grape, Big Brother and Country Joe.”

A landmark 1967 music and Summer of Love commercial and cultural validation event in Southern California occurred on September 15, 1967: Bill Graham Presents the San Francisco Scene at the 18,000-seat Hollywood Bowl with Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, and Big Brother & the Holding Company.

This Graham-stage rental further cemented the Hollywood and Haight Asbury relationship that earlier was partially forged by two June weekends: One in Marin County. The Mt. Tam Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival and the other the Monterey International Pop Fesitval.

“We were pretty scared,” Pete Townshend emailed me in 2007 for a MOJO magazine article on the 40th anniversary of the Monterey gathering. “We’d done a package in New York City with Cream, and it seemed as though we’d missed a beat. We were still displaying Union Jacks and smashing guitars, while Cream played proper music and had afro haircuts and flowery outfits. Jimi had already hit in the U.K.

According to Townshend, “This was a divine opportunity. A side issue was that we played at the Fillmore on this trip, and that was probably more important to us, because Bill Graham insisted we play a longer set than we were used to. So we had to really begin to play proper music, like Cream I suppose. It was around this time we began to include songs like ‘Young Man Blues’ and ‘Summertime Blues.’”

“The festival was incredibly busy, productive, life-changing, exhilarating and relaxed; I do not think that ever happened again,” my pal Andrew Loog Oldham told me in 2007. “The focus was incredible; the mission was God-given. We had never been given that type of responsibility before and there was no way our side was going to be let down. Monterey Pop gave service; it still does. I remain oh, so proud I was there and was a small part of it. Otis, the Who, Jimi Hendrix—every time I think of the music I remember the sea of faces and the rhythm-of-one of the crowd. These white kids in the audience were in school. We all grew from the diversity presented in those three days.”

What many people and historians fail to realize at the time of the September 1967 Graham Hollywood Bowl booking, why the Bay area music acts even played locally and then spread nationally, was due to a meeting of approximately 60 managers and artists demanded with Chet Helms and Howard Wolf, the talent buyer from 1966 to 1971 for the Avalon Ballroom and Family Dog.

“They were really dissatisfied with artists from Los Angeles being presented at the Avalon and coming into their San Francisco scene,” recalled Wolf in a 2015 interview. “This goes back to 1966 with the Grass Roots. And now the Doors are at the Avalon. The problem was one-sided. Los Angeles and Hollywood loved San Francisco. But San Francisco didn’t love Los Angeles.

“They were really dissatisfied with artists from Los Angeles being presented at the Avalon and coming into their San Francisco scene,” recalled Wolf in a 2015 interview. “This goes back to 1966 with the Grass Roots. And now the Doors are at the Avalon. The problem was one-sided. Los Angeles and Hollywood loved San Francisco. But San Francisco didn’t love Los Angeles.

“After asking a number of artists where they were born, and how long they had actually lived in San Francisco, it was apparent that virtually no one was born and raised in San Francisco. They had migrated from other cities like San Diego, Chicago or Detroit. They said that they could perform in San Francisco but no one else could come—i.e., Los Angeles.

“I asked them if they would like to perform in other cities across the country. They virtually all said yes. “How do you think you could do that,” I asked? I then explained one of the reasons they could, is that I would bring artists from the city they were from, and put the San Francisco artists on the bill, and both would be on the poster. When the poster went back to that city, that’s how they would be recognized. Russ Gibb, a DJ from Detroit, had seen what was happening in San Francisco at the Avalon and the Fillmore and wanted to do something like that at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit.

“A year later the Doors are No. 1 all summer and fall with ‘Light My Fire.’ Just before they had a hit record, I arranged for the Doors to play the Avalon over a weekend. It was a big step in setting up the Los Angeles music to San Francisco pipeline. These are the artists I brought up in 1966 from L.A: Love, Sons of Adam, Leaves, Grass Roots, Captain Beefheart, Buffalo Springfield. In 1967 I also brought up Lee Michaels, Sparrow, Other Half, Doors, Chambers Brothers, Taj Mahal, and Canned Heat.

Wolf was also highly instrumental in steering talent to a new music spot opened on Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood called the Kaleidoscope in spring 1967. Initially, the Kaleidoscope was a rotating psychedelic dance club operated by John Hartmann (later to manage Crosby, Stills and Nash), Skip Taylor (manager and record producer of Canned Heat) and Gary Essert (later to found and helm the Filmex Festival).

The trio presented Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, the Peanut Butter Conspiracy, the Doors, Canned Heat, and the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band. The operation found a more permanent home at the former site of the Moulin Rouge and later the Hullabaloo on Sunset Blvd. The team fixed up a building, across the street from the Hollywood Palladium, installed light show and a new sound system.

“Skip Taylor and I were agents and left William Morris,” stated Hartmann, “because they wouldn’t let us open a San Francisco office once we saw what was going on there in 1966. And we said, ‘Let’s rent a house, sign up all these acts that are gonna be huge.’ And that was when we started the Kaleidoscope club. In April of 1967, we brought the Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead and Canned Heat together on the same bill at a Kaleidoscope show.”

Future Kaleidoscope shows headlined Canned Heat, Sly & the Family Stone, Big Brother & The Holding Company, Spirit, Love Byrds, Taj Mahal, Eric Burdon & the new Animals, Traffic, Doors, James Cotton Blues Band, Sons of Champlin, Fever Tree, Pacific Gas & Electric, Bo Diddley, Clear Light, Steppenwolf, Quicksilver Messenger Service and a riveting matinee I caught with the Mandala from Canada.

The Aragon Ballroom, where the Venice and Santa Monica beaches meet, had been a big-band outpost in World War II. In the 1950s, it became Lawrence Welk’s home base, then briefly served as a residence for Dick Dale’s surf guitar in the early ’60s. The owner of New York’s wildly popular Cheetah expanded his reach and opened a West Coast branch there in February 1967.

“The Cheetah was a short-lived and prescient chapter in Los Angeles rock history,” as Kirk Silsbee outlined to me. “A psychedelic ballroom with acres of dance floor, multiple couches, a corrugated metal wainscot and two four-foot-high stages that sat side by side, it had as its only competition the Sunset Strip’s Kaleidoscope club. The considerable distance from Hollywood and subsequent attendance falloffs were a continual problem.

“The bills included the Young Rascals, Eric Burdon and the Animals, Hamilton Streetcar, Jefferson Airplane and the Doors (on the same show), the Byrds, Love, the Chambers Brothers, Iron Butterfly, the Grateful Dead, Kaleidoscope, Clear Light, Bo Diddley, Smokestack Lightning, the Seeds, James Brown’s Revue, the Turtles, Captain Beefheart, Larry Williams and Johnny “Guitar” Watson, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Ike and Tina Turner, the Merry-Go-Round, the Fugs, Mandala, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, Sly and the Family Stone, the Steve Miller Band, Howlin’ Wolf and H.P. Lovecraft. The Electric Flag, Country Joe and the Fish, Pink Floyd, Traffic, Ten Years After and Creedence Clearwater all played their first SoCal bookings at the Cheetah.

“Buffalo Springfield and the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band shared an improbable bill. Arizona transplants the Spiders became the house band. They changed their name to the Nazz, before they changed it to Alice Cooper. The Cheetah was where Pink Floyd played the second and last night of its aborted first American tour.”

“Bob Gibson, who was involved in the Venice Cheetah, brought me into the Cheetahs,” reminded Howard Wolf. “The Whisky a Go Go was 21-and-over admission for most of 1967. The Kaleidoscope did not even have a beer or wine license or even serve food. Kids could attend the shows. One other reason why the rock music of 1967 found an initial live audience on the West Coast that turned into a record-buying element was, 98% of the people going to the Avalon, the Fillmore, the Kaleidoscope in Hollywood, the Cheetah at Venice Beach and shows at the Los Angeles Shrine Exposition Hall in 1967, was that tickets were sold night of the event at the door and early-evening walk-up purchase at the box office.

“This is a world before record labels provided tour support and thought in three-album deals. There might have been one or two record stores selling tickets or a psychedelic head shop selling tickets where posters had been dropped off. There were devoted people paying $2.50 or $3.50 a ticket to see and discover these bands; many didn’t have major-label record deals.”

Beginning in 1966, with a Jefferson Airplane and Paul Butterfield Blues Band pairing, Bill Graham began to rent San Francisco’s Winterland for concerts, a bigger room, and after closing the Fillmore West in 1971, he started having weekend shows on a regular basis.

Many live albums were recorded at Winterland: Big Brother and the Holding Company Live at Winterland ’68, Live Cream Volume 11, Jefferson Airplane Thirty Seconds Over Winterland, The Complete Recordings Jimi Hendrix Live at Winterland.

One thing all the West Coast music halls and club owners had in common, and it obviously extends to the Ash Grove and Troubadour in West Hollywood, were the appearances of touring blues musicians. Going back to September and October of 1966, there was an entire series of San Francisco Winterland dates with Jefferson Airplane, Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Muddy Waters.

“I was part of the generation when everyone took LSD to watch the Grateful Dead,” observed Marshall Chess in a 2006 interview. “I did. I’ve been at the Fillmore West sitting on the floor. And it blew my mind. Bill Graham was the greatest for that for the blues artists of that era. B.B. King and Muddy Waters on the bills. FM radio was a Godsend for the blues. The big commercial AM stations would not play the records at all except some black stations.

“FM radio and the free-form formats, and Tom Donahue’s vision was the spice in the cake. You get it? So FM radio was a spice. When FM radio hit, that was a whole other thing. I drove around the U.S. visiting alternative FM radio stations. You could go right into the control room and they’d put your albums right on! That was a crazy time. The seed of it, in my mind.

“Muddy on stage and in the studio was the best,” Marshall exclaims. “He was organized. He was a fuckin’ leader. I always say this. People say, ‘What do you mean?’ He was a fuckin’ leader. Muddy was the reincarnation of a tribal chief, of a president, of a king. Such a powerful presence. I just loved him. And he treated me so good. He used to call me his white grandson. His wife Geneva used to send me fried chicken wrapped in foil. Muddy once wrote a poem to a girl for me that I gave when I was in high school. Muddy Waters and B.B. King really dug white people doin’ their stuff. Sonny Boy [Williamson] was very much into white people doin his stuff.

“So, when Muddy’s Electric Mud LP came out, I had a very good group of radio people and sent it around. My alternative guys. And they all got on it heavy. So the album took off and blew up. I think we shipped 100,000 units in the first month. It was the biggest album Muddy had ever had. A blues album at that time. And everyone loved it, including Muddy. We were in the record business and we liked that it was selling, ya know.

According to Chess, “Howlin Wolf…On stage very commanding, but off stage a very gentle and soft man. I remember him telling me he was learning how to read music. Did you know that? He went to school to learn how to read music so he could learn how to play the guitar. He wanted to learn notes. One time my dad had me bring him a thousand dollars to his house, and he opened like those tool boxes that you lift off the tray at the top. And it’s stacked full of money. ‘What do you need this money for?’ ‘I gotta go buy some special dogs to huntin’ in my farm.’(laughs).He was a gentle man but ferocious. Big. He used to drink a lot. He was pretty much high a lot when he performed. I remember (Eric) Clapton gave him a fishing rod. Wolf was a real sportsman.”

The Fillmore and Avalon also gave a platform to blues-infused acts Canned Heat, Love, the Steve Miller Blues Band, James Cotton, Magic Sam and Chuck Berry, while a few Winterland concerts featured Jimi Hendrix , Soft Machine, Albert King and John Mayall.

“In 1968 I hired Mick Taylor for the guitar position and decided at that time to add horns to the lineup,” remembered John Mayall in a 2015 email exchange, “which broadened the scope of the songs we played live and enabled me to extend the blues catalog. Horn players usually have a jazz background, and this was a helpful element to add to the quartet format.

“The British musical press at this time wasn’t giving enough attention to some of the American great bluesmen, and I wanted to give the fans clues as to where to broaden their knowledge of great but sometimes neglected performers. It was a way also to make the British press aware of what was going on under their noses.

“I was of course aware that FM radio stations in the U.S. were playing my records, which all helped to spread the word about what I was doing for the blues. Probably helpful for me to be in demand enough to do my first U.S. tour in January 1968.” By 1967, the Shrine Auditorium building in downtown Los Angeles had opened its doors to rock ’n’ roll. It became a critical stop for bands working the Fillmore or ballroom circuit.

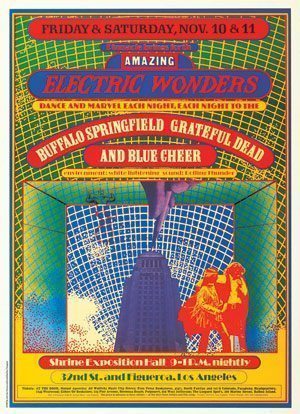

Christened the “Pinnacle” dance concert series, the adjacent Shrine Exposition Hall adds names like Buffalo Springfield and the Grateful Dead, and in 1968 Hendrix and Traffic, alongside the cavalcade of Hollywood stars who have graced its venerable stage. I attended a handful of Pinnacle gigs in 1968. My ears are still ringing from the Vanilla Fudge.

Christened the “Pinnacle” dance concert series, the adjacent Shrine Exposition Hall adds names like Buffalo Springfield and the Grateful Dead, and in 1968 Hendrix and Traffic, alongside the cavalcade of Hollywood stars who have graced its venerable stage. I attended a handful of Pinnacle gigs in 1968. My ears are still ringing from the Vanilla Fudge.

In my 2014 book, Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972, (Santa Monica Press). Kirk Silsbee best described the action at these incandescent happenings.

“Only fourteen concerts in all,” Silsbee wrote. “The Shrine Exposition Hall was a trade show space, and its use for dance concerts [was] ground that had already been broken by the Freak Out! concerts of July and September 1966, by Frank Zappa. It seemed to be a place where would-be concert promoters grazed; the Doors had already played there in January of 1967, with Iron Butterfly and Sweetwater.

The first of the Pinnacle concerts came in November of 1967, and that wonderful poster by John Van Hamersveld promised “Amazing Electric Wonders” with Buffalo Springfield, the Grateful Dead, and Blue Cheer. “It’s important to remember that the Pinnacle shows were dance concerts. There was an ordinance that barred dancing in Sunset Strip clubs like the Whisky. But people could dance at the Cheetah in Venice and at the Pinnacle shows, and that’s one of the reasons they were so successful. Pinnacle was not the Fillmore South. There were only fourteen concerts, and sometimes it was months between shows. Pinnacle didn’t feel the need to present every weekend, so the bills didn’t have a lot of no-name bands.

“They presented Hendrix, Cream, the Who, Traffic, the L.A. debut of the Jeff Beck Group, the Chambers Brothers, Pink Floyd, Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, and the Yardbirds’ last L.A. appearance. One bill had the Butterfield Blues Band, the Velvet Underground, and Sly and the Family Stone. That show covered a lot of stylistic ground! It was music that was too big for a club, yet it preceded the era of arena and stadium rock.

“The second show with the Moby Grape, Country Joe and the Fish, with Blue Cheer and the United States of America went well, and the light show expanded using Hugh Romney and the Hog Farm Family’s psychedelic light show. We hired Thomas Edison Lights and film students Caleb Deschanel, Taylor Hackford and George Lucas from University of Southern California Film School and Pat O’Neill and Burt Gershfield from the UCLA Film School with movies. As a fan and concert promoter with Pinnacle, often the music and the event posters created in 1967 were the backdrop to all media, clothing and record stores, on the FM radio stations.”

And when re-visiting and examining West Coast albums that changed your life, don’t forget one man who taped some of the action: Engineer Bill Halverson recording credits during 1966-1969 include the Beach Boys Wild Honey, Chuck Berry Live At The Fillmore, where Chuck was backed by the Steve Miller Band. He also worked at The Monterey International Pop Festival, assisting studio owner Wally Heider and producer Bones Howe that weekend, and personally recorded Ravi Shankar’s cosmic set. In 1968, he was an assistant on Johnny Cash’s Live at Folsom Prison, and engineered the basic tracks of Cream’s “Badge,” capturing the guitar duet of Clapton and George Harrison. In 1969 Halverson engineered the first Crosby, Stills and Nash LP also at Heider’s facility in Hollywood.

“The Monterey International Pop crowd was a completely different crowd than the Monterey Jazz festival. I hadn’t done the Haight Ashbury thing and all the light shows,” admitted Halverson.

“At the time I was not too fond of the music yet, either. And the thing that really changed me was doing Cream because that was a jazz band. In reality, it is a rock ‘n’ roll band but for me at that time it sounded like a jazz band just ‘cause of all the free form stuff. Tom Dowd showed up and I thought he was gonna engineer it. And we set up for up for the sound check and they had had a real struggle with everything distorting when they tried to record them in England and New York.

“When I first opened up the mike on the amps it was distorting. And I finally found this place by accident in between the four speakers of a Marshall stack where it was just up against the grill cloth. And it was clean. And the side benefit when we played it back was that Eric’s guitar sounded like it was in a separate room, ‘cause the four speakers like acted like a baffle.

“Ginger Baker reminded me of a real good jazz drummer. He had two kick drums and all those cymbals and toms. Heider had a way of just putting a couple of Sony C-37 tube overhead and a couple of microphones on snare and hi hat and kicks. Heider also had this pair of Neumann 67 tube microphones that he had a knack for placing them for audience mikes but keeping them out of the way of the PA and doing that. I used those same 67’s at Fillmore and everywhere else for audience.” Ironically, the gatefold of Cream’s Wheels of Fire lists “Crossroads” misleadingly printed as “Live at the Fillmore,” when the track was recorded at Winterland.