Rick Rubin And A Punk Band Called Hose: How A 12″ EP Helped Build An Empire

The band’s 12-inch was the first release with a Def Jam logo.

Rick Rubin is best known as a producer-extraordinaire who has crafted hits for hip-hop luminaries, including Jay-Z, Kanye West, and LL Cool J. But 30 years ago, he was an impressionable white kid from Long Island who changed the face of modern Black American music. It’s an ironic thought – but it happened. “Before Def Jam, hip-hop records were typically really long, and they rarely had a hook,” Rick Rubin told The New York Times in 2007. “By making our rap records sound more like pop songs, we changed the form.” He had a passion for catchy songwriting and melodies and used radio-friendly formulas – by the likes of The Beatles and The Monkees – to create structure. His approach ultimately catapulted hip-hop into the mainstream. But long before this was a conceivable thought, he found himself in American hardcore punk.

Rick Rubin and punk

In 1981, Rubin, an NYU freshman barely in his 20s, did what any music-obsessed fan would do. He picked up a guitar and along with some friends (bassist Warren Bell, drummer Joel Horne, and lead singer Rick Rosen) formed the artcore band, Hose. The band moved in similar DIY circles as fellow punk artists Beastie Boys. And it’s no secret Rubin had a knack for creating. Before Hose, he spent his teens in Lido Beach, New York learning the basics from high school music teachers and formed another punk band called The Pricks who gigged at the East Village hangout, CBGB. Once Hose came about, what resulted was an eponymous debut 12″ EP, released sometime in April 1983 and served – albeit indirectly – as a catalyst for a little-known record label he’d create out of his 712 dorm room over at Weinstein Hall: Def Jam Records.

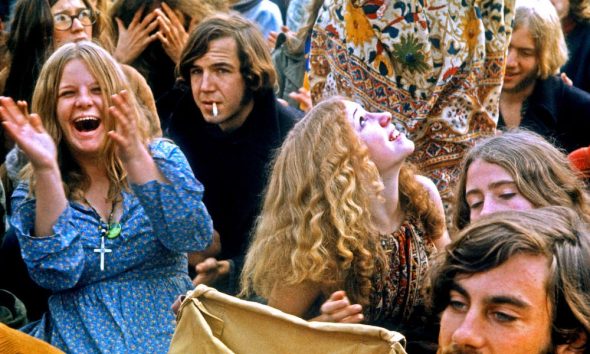

Punk rock is the nonconformist’s playground. Up until hip-hop stole the show, punk’s brazen stance made it a rebel in the crowd. As a subculture, it was more than just music; it was an anti-establishment mindset. Rubin, a music rebel in his own right, managed to finesse both worlds. “I was the only punk rocker at my high school and there were at least a handful of black kids who liked hip-hop,” Rubin told Newsweek in 2013. “Both were kind of the new music of the day, and it was lonely being the only punk. Because of where I lived and because there was no community to be a punk with, I started hanging out with the kids who liked hip-hop. And I learned about it through them.”

Compared to the sexed-up sound of 70s disco, New York’s 80s punk was messy and read like entries from a diary. “I was listening to The Clash and the Sex Pistols [from the U.K.], but it wasn’t really until American hardcore punk bands like Minor Threat and Black Flag [that punk started to resonante]; those bands felt more relatable to me,” Rubin told Zane Lowe in 2014. “They were talking about more personal stuff whereas the English bands tended to talk more about class struggle; things that we didn’t really experience here in America.”

Punk, though not mainstream, spread through America and all over the world – especially in Australia and the UK. It was filled with the kind of angst that throughout the decades came to define underground youth. Black punk bands like Bad Brains and Pure Hell, though iconic, were still relegated to underground status. “We used to hang out at this spot, the Rat Cage. Rick Rubin used to come through,” Bad Brains bassist Darryl Jenifer said in a 2007 interview. “He was kind of scared of me, too. He didn’t really like the Bad Brains, Rick Rubin. Everybody used to be trippin’ on us, and he wasn’t feelin’ us. He was into Slayer.” The same level of passion found in punk exists in hip-hop; this may explain why the rappers making waves now are more punk than the familiar ‘hip-hop’ archetypes earlier artists were accustomed to. Ultimately, though, both genres are in fact cut from the same cloth, and Rick Rubin became a bridge-builder of sorts. He propelled hip-hop from the inner city into the cassette players of white kids from the suburbs. Whether or not the inevitable crossover helped or hurt the genre remains up for discussion.

The Hose 12-inch

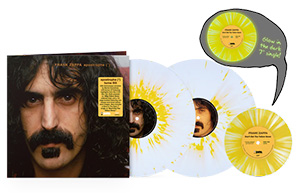

The exact date the Hose 12″ EP arrived remains unknown. Its sleeve jacket paid homage to modern artist Piet Mondrian’s famous work Composition II. According to Rubin, the cover art represented the bass and drums providing structure while the vocals added color. But you can’t help but notice the cover’s most understated feature, strategically placed in a yellow box on the bottom: the Def Jam logo. A trademark that would later become an unequivocal symbol of power in the urban music industry.

As Eric Hoffer, Rubin’s former classmate, told New York Magazine, Hose was “… crazed, almost Charles Manson–like. They were pretty awful.” This paints a picture of someone possessed; slashing away at music like a scene from a horror film. Hoffer also expressed feeling confused by Rubin’s agenda for Hose. “People couldn’t make sense of what he was onto – the fact that he was in this band, and then he’d come back from these hip-hop clubs at night,” he said. For Rubin, punk had sentimental value. “I always played and felt like I always wanted to be part of it,” Rubin told Zane Lowe. “I never felt like I was particularly good at any part of it but I enjoyed it and was passionate about it.” Hose sounded amateurish, because, well, they were. Yet, they made it happen. They created an EP with a single microphone in a dorm activity room, and it was a rather brave feat.

Take its opening track, “Only the Astronaut Knows the Truth,” a cacophonous mixture of drums, and unrefined guitar strokes that are at war with the singer’s monotone screechy voice. What saves the track is a calm bass riff heard from beginning through to end, giving the song a clearer focus. The textures throughout the song are almost reminiscent of Kanye’s most divisive album, Yeezus, which Rubin executive produced, and features a polished roster of mixers, sound engineers, and instrumentalists. You can spot it on “Black Skinhead,” where Ye tries to push the blur the lines between punk rock, metal, and hip-hop. Punk also exists, as Rubin suggests, on “Bound 2.”“I removed all of the R&B elements leaving only a single note baseline in the hook” Rubin explained to The Wall Street Journal. “We processed [the hook] to have a punk edge in the Suicide tradition.” Like the Hose 12″, Yeezus, though it received exceptional reviews from music critics, wasn’t as embraced by a wider audience. In Ye’s case, the resistance stems from fans still clinging to his College Dropout days – when Ye was “real hip-hop.” But the outcome for both was about experimenting with sounds.

Each track on 12″ blends seamlessly into the next, as if the band recorded the project in one take. There’s a message on the second track, “Dope Fiend” that shouldn’t be taken at face value. Rosen doesn’t say much beyond the track’s title, but it paralleled the growing concerns about the rising crack epidemic that swept the country and affected inner-city black neighbourhoods during the Reagan era. “Dope Fiend” wasn’t as poignant as Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message” or “White Lines,” but the band chimed in on a contentious topic, when Mr. and Mrs. President were convinced with their War on Drugs campaign that all everyone needed to do, was “just say no.” Laughable at best.

The band’s respect for black music and its artists was apparent. Their rendition of Rick James’ “Super Freak” is a jam. They put a seductive spin on the track without trying to outdo the original. Listen to this redux in a seedy dive bar now or at a music festival like Afropunk, and it’s cool to hear a synth-heavy funk classic, drenched in lust and machismo, remodeled and stripped in post-punk fashion. While “Fire” is neither here nor there, by the EP’s closing track, “You Sexy Thing” a remake of the Hot Chocolate’s disco original, isn’t completely dissonant from what was trendy in underground punk then. The Hose 12″ is flawed, but it was a brilliant passion project and set the stage for Rubin’s path as a mega-producer and cultural composer. The band had New York’s indie movement as a backdrop. The project was Rubin’s blueprint.

The launch of Def Jam and beyond

What’s interesting is the Hose 12″ came two years before Run-D.M.C.’s 1984 debut. This was the year when an array of creatives throughout New York came together to exchange ideas, forming a common ground. This was also when Rubin officially launched Def Jam Recordings with Russell Simmons, and a year after that, played an instrumental role in mixing the rap trio’s Billboard-charting “Can You Rock It Like This” single from their King of Rock album. By then, Rubin’s aesthetic had evolved into proper Rock & Roll, which was a sign of the times. Rock was the reckoned force, thanks to massive acts like Aerosmith and Motley Crue. Rock, unlike punk, which become stagnant as music evolved, was easier to place into a hip-hop context; it was the most popular genre in music.

As hip-hop rose to prominence, maybe it was inevitable that a free spirit would succumb to mass-corporatization. Perhaps that’s what happens when the objective moves away from creativity in favor of “getting the bag.” But obviously, that level of scale must have got to Rubin. “[Russell and I] had this incredible success over a five-year period. Wild success. And in the growth, when things get big, it gets very confusing,” Rubin told Zane Lowe. “And our interests were different. I always cared about making great music, period. And Russell always cared about being a successful businessman. And sometimes those roads didn’t go together. When I understand his business reason for it, he was right. But my nature was ‘it’s gotta be about the art.’ In 1994, he left Def Jam and hip-hop, but not before holding a funeral for the word ‘Def’ following its inclusion into Webster’s dictionary. Entertainment Weekly’s eulogy, published in 1993, states: “Rev. Al Sharpton, flanked by four armed guards, delivered a moving eulogy: ‘Def’ was kidnapped by corporate mainstream entertainment and returned dead. When we bury ‘Def,’ we bury the urge to conform.” In hindsight the funeral was symbolic of many deaths; for instance, it was the ’90s; hip-hop was now synonymous with MTV despite being dangerously territorial, white boy bands were serious business, and punk died, unless you listened to Green Day. Music and its movements were heading into pop mode. A far cry from Rubin’s formative years.

Rubin went on to head-up American Recordings, working within the hard rock, metal, and country music spaces, before finding himself right back in hip-hop/Def Jam’s grip, and producing Jay-Z’s banger, “99 Problems” in 2003. Apparently, old habits do die hard. This track emphasized hip-hop’s ability to be punk rock via a hardcore East Coast beat at a time when the genre was in limbo, unsure of the direction it was heading. The collaboration was an ironic but pivotal moment for both artists, as this marked Rubin’s triumphant return to the game just as Jay-Z – at least at the time – was on the way out.

The Hose 12″ must be parked somewhere in Rubin’s psyche, as its remnants can still be heard throughout his prolific career. Maybe, you’d object and say, ‘No.’ His influence clearly starts with Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill or Run-D.M.C.’s Raising Hell. But he was never as pure or as influential than when he was that young blood stirring up ruckus in his dorm room with his mates. When sounds and ideas, like the ones heard on Hose’s 12″, didn’t make sense, but just kind of fell into place. “It was complete punk rock,” Rubin told Zane Lowe. “And the initial energy of Def Jam was a more urban version of punk rock. That’s how we saw it; the records I was making at the time, was punk rockers making hip-hop.”

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2018.