The Band’s Best Songs: 20 Classic Rock Gems

From their 1968 debut album to ‘The Last Waltz,’ the group made some of the defining music of their generation.

According to guitarist and songwriter Robbie Robertson, The Band’s name was a practical choice. “When we were working with Bob Dylan and we moved to Woodstock, everybody referred to us as ‘the band,’” Robertson recalled in The Last Waltz, Martin Scorsese’s 1978 documentary about The Band’s farewell concert. “He called us the band, our friends called us the band, our neighbors called us the band.”

In truth though — and Robertson knew this better than anyone — the band’s name was a statement; a bold declaration of talent and musicianship that also spoke of a back-to-basics approach at odds with the psychedelic fashions of the day.

The Band were good enough to live up to it. The five members — Rick Danko (bass, vocals, fiddle), Levon Helm (drums, vocals, mandolin — the only non-Canadian), Garth Hudson (keyboards, accordion, saxophone), Richard Manuel (vocals, piano, drums) and Robertson (guitar, backing vocals) — served their musical apprenticeship as The Hawks, Ontario-based rockabilly wildman Ronnie Hawkins’ backing band. Helm joined Hawkins’ band straight from high school in 1958. Two years later, the then-15-year-old Robertson was recruited, followed shortly after by Danko, who was a year his senior. Manuel arrived in the summer of 1961, and by the end of that year, Hudson was on board. The Hawks tore through clubs and dive bars, becoming a well-oiled rock ’n’ roll machine, but early in 1964, dissatisfied with their wages and feeling creatively held back, the Hawks handed Hawkins their notice.

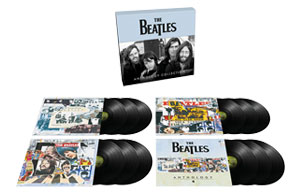

Order The Band’s The Best of the Band on vinyl now.

They went it alone, first as The Levon Helm Sextet (featuring saxophonist Jerry Penfold), before spells as The Canadian Squires and Levon & The Hawks, while touring as hard as ever. Their big break came when Mary Martin — then working as an assistant to Bob Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman — recommended The Hawks to Dylan, then on the lookout for an electric backing band. In late 1965, The Hawks backed Dylan on his rambunctious single “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” and — except Helm, who left to work on an oilrig — were called upon for the 1966 tours of North America, Europe, and Australia. The shows were split between Dylan solo acoustic sets and thrilling electric sets, causing extreme reactions from factions of the audience keen to see Dylan remain in the folk singer box he’d long since outgrown.

In early 1967, The Hawks (still minus Helm) moved to Woodstock, where Dylan was recuperating following a motorcycle crash and on a hot writing streak. Danko, Hudson, and Manuel lived in Big Pink, while Robertson lived nearby with his wife. Eventually, Helm was persuaded to rejoin his old bandmates. Big Pink soon doubled up as a basement and recording studio. Robertson told this writer in 2019, “We were just having such a great time together and, because we had this little tape machine, we were able to document some of the great times we were having. Some of them were done in jest and having fun and some were recorded because they turned out to be beautiful songs.

“The lack of pressure was so wonderful; it’s such a rare thing to be able to feel something that is just about joy… We didn’t think that the majority of that music would ever be heard outside of the basement.”

Since then, every existing minute of the music Dylan and The Band made in the basement has been released and pored over by fans, while dozens of the songs that emerged from Big Pink have become classics. What’s more, the atmosphere of heady creativity kickstarted a career for The Band away from their mentor. From their 1968 debut album, Music From Big Pink, to The Last Waltz, The Band gave us some of the defining music of their generation. Here’s our pick of their 20 best songs.

20. This Wheel’s On Fire (Music From Big Pink, 1968)

“I realised that Bob had been coming every day for six or seven days a week,” Rick Danko told MOJO’s Barney Hoskyns in 1995, reflecting on The Band’s early days in Woodstock. “If we were sleeping, he’d get us up, he’d make noise and make some coffee, or bang on the typewriter in the living room on the coffee table. Maybe 150 songs were composed in about a seven- or eight-month period.”

One of the most enduring basement songs was the collaboration between Danko and Dylan, “This Wheel’s On Fire.” Danko suggested that he wrote the music and verse melody, Dylan contributed the lyrics, and they wrote the chorus together — the song’s inventive use of diminished chords certainly backs up Danko’s claim. Meanwhile, Dylan’s lyrics are at once plain speaking and unsettling — its verses carry a threatening tone, with the narrator reminding an unnamed partner of an inextricable (and perhaps eternal) bond, while the striking image of the chorus (“This wheel’s on fire/Rolling down the road”) is loaded with biblical imagery. The basement version of “This Wheel’s On Fire” was a doomy country shuffle, but The Band’s version, a highlight of Music From Big Pink, quickens the tempo and ramps up Garth Hudson’s trippy organ sound to create an intoxicating atmosphere, echoed by Danko’s increasingly frantic-sounding vocals.

19. The Rumor (Stage Fright, 1970)

“It was a dark album, and an accurate reflection of our group’s psychic weather,” Levon Helm says of The Band’s third album, Stage Fright, in his 1993 autobiography This Wheel’s On Fire. Nowhere was this more apparent than “The Rumor,” a song written by Robbie Robertson about the gossip spreading around Woodstock about members of The Band experimenting with hard drugs. But despite being fuelled by paranoia, “The Rumor” was one of the album’s highlights, with strong vocal performances from Danko, Helm, and Manuel and one of the most satisfying grooves they’d commit to tape.

Click to load video

18. When You Awake (The Band, 1969)

The success of Music From Big Pink meant its follow-up was highly anticipated. Keen to avoid record label interference and yearning for the informality of the basement, The Band took the then-radical step of building their own studio. They spent a month setting up a studio in the pool house of a mansion in the Hollywood Hills, once owned by Sammy Davis Jr, while living together in the main house. Their instincts proved correct; the resulting self-titled album has a sense of relaxed bonhomie they’d struggled to find in an expensive studio.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Robbie Robertson and Richard Manuel’s “When You Awake,” a countrified charmer in two parts sung by Rick Danko. It begins with Robertson’s unhurried, casual guitar and an organ line from Garth Hudson that has the warmth of early morning sunshine hitting your face. A story unfolds of a young boy seeking advice from his grandfather. “It’s about someone who passes something on to you, and you pass it on to someone else,” Robertson said in Barney Hoskyns’ Across The Great Divide. “But it’s something you take to heart and carry with you your whole life.” In this case, words of grandfatherly wisdom are passed on and sung in unison by Danko, Manuel, and Levon Helm, underlining the vocal prowess The Band had at their disposal. Halfway through, there’s a seamless segue into what may originally have been a totally different song, with a young man boasting of dates and despairing of the frosty weather. It fades out abruptly, leaving the listener leaning in, wanting more.

17. Ophelia (Northern Lights – Southern Cross, 1975)

Come the mid-70s, The Band were in trouble. Disputes over royalties and worsening alcohol and drug problems had weakened the brotherly bond forged by years on the road. Meanwhile, Robertson’s songwriting lost some of its sparkle on 1971’s Cahoots, and the rest of The Band barely contributed. Their musicianship was never in question, though, thanks to the stunning live album Rock Of Ages (1972), the lively covers set Moondog Matinee (1973) and backing Dylan on 1974’s underrated Planet Waves and a record-breaking joint tour.

Looking to recapture the old magic, in 1974, The Band set up Shangri-La, a state-of-the-art recording studio in Venice Beach, where they recorded Northern Lights – Southern Cross. For the first time, the material was entirely written by Robertson, while Garth Hudson’s embrace of synthesizers gave it a polish their earlier records kicked against — but still, Northern Lights – Southern Cross showed flashes of greatness. “Ophelia” was one such example, an irresistibly funky take on Dixieland jazz with a horn arrangement put together single-handedly by Hudson in the studio.

The Ophelia in question has split town in a hurry, and it’s eating the singer up inside — he can’t wait for her to return and doesn’t care who knows it. Robertson knew that such a lyric called for the lusty charisma of Levon Helm. “It had his name written all over it,” Robertson wrote in his 2019 autobiography Testimony. “I loved the way the track felt after we cut it. The combination of horns and keyboards that Garth overdubbed on this song was one of the very best things I’d ever heard him do. ‘Ophelia’ became my favorite track on the album, even if it didn’t have the depth of some of my other songs. The pure, jubilant pleasure of that tune swayed me.”

16. Rag Mama Rag (The Band, 1969)

One of The Band’s secret weapons was their ability to switch things up — if the track’s not working, why not play musical chairs? The storming “Rag Mama Rag” saw Rick Danko swap the bass for fiddle, vocalist Levon Helm putting his drumsticks aside to play mandolin, Garth Hudson moving from behind his bank of keyboards to an upright piano, and Richard Manuel keeping time on drums rather than playing piano. Robbie Robertson was the only member to stick to his usual instrument — electric guitar — while producer John Simon added tuba.

It was an unlikely set-up, but the lascivious rocker gave The Band their biggest hit single in the UK, reaching No. 16. As with so much of the self-titled album, it’s timeless — Danko’s fiddle playing is straight out of Nashville; Hudson’s ragtime piano is an utter delight — and unfeasibly exciting.

15. Tears Of Rage (Music From Big Pink, 1968)

Another Dylan co-write from that productive summer in Woodstock, this time with Richard Manuel, “Tears Of Rage” was the opening track on Music From Big Pink and most listeners’ introduction to The Band. They play it as a slow-burning funereal dirge, with Robertson’s heavily phased guitar in conversation with Manuel’s anguished falsetto, which wrings every drop of emotion from the lyrics; a remarkable feat considering he was unsure as to their exact meaning.

“[Dylan] came down to the basement with a piece of typewritten paper,” Manuel recalled in a 1985 Woodstock Times interview, “and he just said, ‘Have you got any music for this?’… I had a couple of musical movements that seemed to fit, so I just elaborated a little bit, because I wasn’t sure what the lyrics meant. I couldn’t run upstairs and say, ‘What’s this mean, Bob?’ ‘Now the heart is filled with gold, as if it was a purse.’”

“Tears Of Rage” was also a breakthrough in terms of The Band finding their sound. The engineer in A&R Studios had set the studio up as any modern rock band would — with acoustic baffles between the players for separation so mistakes could be fixed later. The Band were used to hearing, seeing, and responding to one another’s playing, so Robertson asked for the baffles to come down. Although the engineer initially despaired, something magical happened. “John [Simon] says over the talkback, ‘I think we’re getting somewhere, guys.’… We go in the control room and they play back our first take. That was the first time we heard the sound of The Band coming out of those speakers. We looked at one another and, in that moment, we knew we had the confidence, we had our own rules, our own way of making music.”

Click to load video

14. Across The Great Divide (The Band, 1969)

In the ’80s, Robbie Robertson became an in-demand soundtrack producer, working on movies including Martin Scorsese’s The King Of Comedy (1983), Casino (1995) and Killers Of The Flower Moon (2023). But his songs for The Band reveal an instinct for the cinematic which flourished way before Marty came calling. The opening track to 1969’s self-titled album emphasized Robertson’s talent for scene setting and use of dramatic devices (in this case, Chekhov’s gun). It begins with a fearful-sounding Richard Manuel pleading with a woman who seems intent on causing him harm, “Standing by your window in pain, a pistol in your hand/And I beg you, dear Molly, girl, try and understand your man the best you can.” At that point, his buddies all join in, transforming the track into a good-time groove as Manuel recounts a life of roguish escapades. But any idea that Molly will let him get out of Dodge is thrown into question by the final verse and a worried, “Now tell me, hon, what you done with the gun?”

“I knew what these guys could do,” Robertson told Classic Rock in 2019. “I knew who their characters were. And I was writing screenplays for these characters. I thought I was Ingmar Bergman. I was writing for Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann. I thought that was my job. But that’s different than any other group, and it was a different format. Everything was different about The Band.”

13. Life Is A Carnival (Cahoots, 1971)

By The Band’s fourth album, Cahoots, success and celebrity had set in, and Danko, Helm, and Manuel’s hell-raising ways were beginning to take their toll, while Robertson was struggling with a severe case of writer’s block. Much of Cahoots feels like the work of a great band trudging through underwhelming material, but on the New Orleans funk of “Life Is A Carnival,” they sound weightless.

The song’s heady groove was cooked up during a Danko and Helm jam session, and Robertson added lyrics that found parallels between the uncertainty of life and the chaos of a carnival. Figuring that nobody could do syncopated New Orleans horn arrangements like the master, Robertson asked legendary Big Easy writer, performer, and arranger Allen Toussaint to write a horn chart for the song. The Band were long-term fans and had recently been impressed by his production on Lee Dorsey’s 1970 classic, Yes We Can. “They’d heard Lee’s album and they were, I guess, impressed a little,” Toussaint said in 1973. “They’re such good guys, and communications were very, very good. They immediately know where you’re coming from.”

12. It Makes No Difference (Northern Lights – Southern Cross, 1975)

Another example of Robertson choosing the perfect singer for his material came with this heartbreaker to end all heartbreakers, sung by Rick Danko. Speaking to this writer in 2019, Robertson was full of praise for his former bandmate, “Rick might’ve been the best friend you could have in this group; he was so warm and generous in his spirit. There was an openness with Rick, and it came through in his playing, in his singing and everything about him. More so than anybody else in the group, perhaps.” On “It Makes No Difference” that openness allows Danko to inhabit a lyric about post-break-up loneliness and deliver it with fathoms-deep melancholy and total vulnerability. In a 1975 interview with New York Times journalist Robert Palmer, Danko explained how he approached the vocal, “I thought about the song in terms of saying that time heals all wounds. Except in some cases, and this was one of those cases.”

“It Makes No Difference” is one of the greatest tracks on Northern Lights – Southern Cross, but nothing beats Danko’s gut-punch performance of the song on The Last Waltz, an emotional tour-de-force topped off by a jaw-dropping duel between Robertson on guitar and Hudson on soprano saxophone.

11. The Shape I’m In (Stage Fright, 1970)

Following the mature sounds of The Band’s first two albums, audiences who’d seen The Hawks might’ve wondered what became of the wild young rock ’n’ rollers. The stomping “The Shape I’m In” from the third album, Stage Fright, proved they could still cut loose. Backed by tough, driving R&B, Richard Manuel sings from the perspective of a down-on-his-luck rogue living on the fringes of society (“I’ve just spent sixty days in the jail house/For the crime of having no dough/Now here I am back out on the street/For the crime of having nowhere to go”). Manuel’s gruff, soulful vocals are a perfect fit for the character — considering the singer’s appetite for self-destruction, it’s easy to imagine that Robbie Robertson wrote it with him in mind. “I always felt very comfortable with Richard in The Band. I knew nobody else had a better singer,” Levon Helm said in 1997. “Richard’s policy was to hold up his glass and say, ‘spend it all!’ — which is a pretty good policy when you think about it.”

10. Up On Cripple Creek (The Band, 1969)

As The Band’s second album took shape, Robbie Robertson was looking for inspiration in the everyday lives of Americans. “We’re not dealing with people at the top of the ladder,” Robertson said in 2022. “We’re saying, ‘What about that house out there in the middle of that field?’ What does this guy think, with that one light on upstairs and that truck parked out there? That’s who I’m curious about.”

“Up On Cripple Creek” was a prime example, a collection of shaggy dog stories told by a road-weary trucker yearning for his woman. “This person, he just drives these trucks across the whole country, and he knows these characters that he drops in on, on his travels,” Robertson added. “Just following him with a camera is really what this song’s all about.”

Levon Helm clearly had the time of his life singing these tales of gambling, drinking, and womanizing, even leading his bandmates in a yodelling session to close the song. Meanwhile, Garth Hudson imitates a jaw harp by playing a clavinet through a wah-wah pedal, and Helm’s drumming and a Robertson guitar lick are so funky that Gang Starr sampled them on 1990’s “Beyond Comprehension.”

Click to load video

9. Chest Fever (Music From Big Pink, 1968)

The supremely funky Big Pink track “Chest Fever” showcased The Band’s ace in the hole, the prodigiously talented multi-instrumentalist Garth Hudson. It begins in spectacular fashion, with Hudson vamping on Bach’s “Toccata And Fugue In D Minor” — a passage he’d extend at live shows to the point where it became a separate song, “The Genetic Method” — before he brings in the rest of The Band with a killer organ riff.

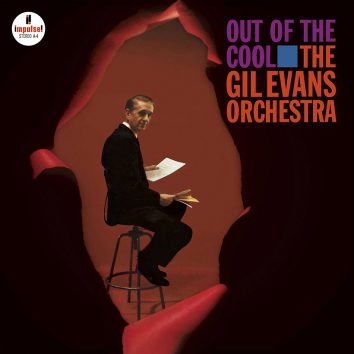

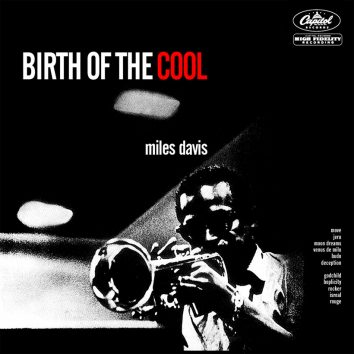

“Garth Hudson was from a different world,” Robertson told this interviewer in 2019. “We’d never witnessed anybody who could do what he does, musically. His improvizing would incorporate so many kinds of music that it was bedazzling. He could’ve been playing with Miles Davis, or a Symphony Orchestra, he just had such a broad horizon when it came to music. He was a very different guy — quiet in personal ways, but not at all in an expressive, musical way. People have said to me over the years, musicians that I really admire in rock ’n’ roll, there was only one Garth Hudson. Still people have no idea how extraordinary this guy really is, so I cherish that. Levon and I wanted him in the group so bad that we begged to have his music help us grow.”

8. Whispering Pines (The Band, 1969)

Though The Band were blessed with some of the greatest voices in rock music, Richard Manuel’s stood out. “We talked about him in the group like he was the lead singer and he hated that, but there was a truth to it,” Robbie Robertson told this writer. “He was the most legitimate singer of all of us; he had the widest range, the most power and everything. The depth of his soulfulness was something that we loved and admired so much.” Manuel’s spellbinding vocal on “Whispering Pines,” which he co-wrote with Robertson, explains the esteem in which his bandmates held him.

Robertson knew from the moment he heard Manuel working on the music that “Whispering Pines” would be special. “Richard had this thing he was playing on the piano, he was hitting this same note over and over again and it almost echoed inside of itself,” he told Rock Cellar in 2017. “Right away, there was this distant, lonely, beautiful, sad feeling to it… In writing the words to ‘Whispering Pines’ I was writing something that I thought Richard could break your heart with if he sings these words.”

7. Jawbone (The Band, 1969)

Manuel’s other major contribution to The Band showed an entirely different side of him. “Jawbone” cast Manuel as another of lyricist Robertson’s wrong-side-of-the-tracks characters; the scoundrel in question could easily be the narrator of “Across The Great Divide,” or a drinking buddy of the trucker in “Up On Cripple Creek.” The verses admonish Jawbone for his bad behaviour and plead with him to clean up his act. His reaction? The totally unrepentant chorus of “I’m a thief and I dig it!,” sung with cathartic joy by Manuel.

Musically, it’s like no other song on the album. Manuel deployed tricksy time signatures (the verses are in 6/4, while the chorus flits between 4/4 and a half-time shuffle), giving “Jawbone” a suitably anarchic feel. Meanwhile, it’s one of the few points on the album where Robertson solo…

6. Stage Fright (Stage Fright, 1970)

The success of Music From Big Pink meant that there was a huge amount of expectation and hype around The Band’s first live shows. Anticipation only grew as they turned down offers from promoters throughout 1968 — unbeknownst to the press, Rick Danko had a car crash, which he was lucky to survive, that put him out of action for months. With Danko fully recovered, The Band eventually booked a run of shows at Winterland, San Francisco, on April 17–19, 1969. But in the days leading up to the first show, Robbie Robertson began to feel so ill he couldn’t stand up. “I felt like I was dying,” wrote Robertson in Testimony. “I couldn’t move… I couldn’t hold any food down… Is this stage fright? Is this all in my head?”

With the show fast approaching and Robertson showing no sign of improving, promoter Bill Graham called in a hypnotist named Pierre Clement. “I was so sick and pining to feel better,” Robertson told Salon in 2020. “I went with it. ‘Please help me and allow me to feel better.’ I said ‘I’ll go under your spell or over your spell. I’ll do whatever you want me to do.’” Eventually, the guitarist made it on stage, though he could barely stand and only lasted seven songs. Turns out hypnosis can’t cure a stomach virus.

Still, the incident fed into the title track of The Band’s third album, Stage Fright. Rick Danko took the lead vocal, investing the tale of a performer “caught in the spotlight” with raw passion. “They gave this choirboy his fortune and fame,” Danko sang, “and since that day he ain’t been the same…” — it’s difficult to believe Robertson wasn’t writing about The Band’s reaction to success.

5. Acadian Driftwood (Northern Lights – Southern Cross, 1975)

Though Robertson spent much of The Band’s career writing about America, “Acadian Driftwood” marked the first time he truly dug into the history of his native Canada. Robertson writes movingly about the British expulsion of around 10,000 French Acadians from their settled lands in 1755, on the eve of the Seven Years’ War, as well as the yearning of the Acadian diaspora for a sense of home. But this is so much more than reportage — in giving voice to the Acadian people, Robertson gives them a dignity that was taken away from them by the rich and powerful so many years ago.

Fittingly, given the gravitas of the song, the lead vocal is shared between Danko, Helm, and Manuel. Still, it’s Danko who takes the evocative final verse, singing in French, “Do you know, Acadia, I’m homesick/Your snow, Acadia, makes tears in the sun.” The music is stirring, given a Cajun flavour — appropriately, as many Acadians settled in Louisiana, eventually contributing to Cajun culture — by Hudson on accordion, piccolo and chanter and bluegrass great Byron Berline’s sorrowful fiddle.

“Acadian Driftwood” was the first step towards later material that explored Robertson’s Indigenous heritage — he was raised on the Six Nations reserve near Ontario — such as the soundtrack to Ted Turner’s film, Music For The Native Americans, and his 1998 album, Contact From The Underworld Of Redboy.

Click to load video

4. King Harvest (Has Surely Come) (The Band, 1969)

Has agrarian tragedy ever sounded funkier? “King Harvest (Has Surely Come)” tells the story of a Dust Bowl farmer on the brink of financial ruin and putting his trust in the union to save him. This guy can’t catch a break — drought has devastated his livelihood, his barn has burned down, and his horse has gone mad — there’s little wonder he’s happy to embrace “a man with a paper and pen, tellin’ us our hard times are about to end.”

“It’s just a kind of character study in a time period,” Robertson wrote in the sleevenotes to the compilation Anthology. “At the beginning, when the unions came in, they were a saving grace, a way of fighting the big money people, and they affected everybody from the people that worked in the big cities all the way around to the farm people. It’s ironic now, because now so much of it is like gangsters, assassinations, power, greed, insanity. I just thought it was incredible how it started and how it ended up.”

Though the ending is ambiguous, there’s an air of desperation to “King Harvest (Has Surely Come),” not least in Richard Manuel’s powerhouse vocal performance, that suggests things won’t end well for the farmer. The feeling of pent-up frustration is felt keenly in the song’s finale, as Robertson brings things home with a stinging guitar solo. “This was a new way of dealing with the guitar for me,” Robertson said in the To Kingdom Come sleevenotes, “this very subtle playing, leaving out a lot of stuff and just waiting till the last second and playing the thing in just the nick of time. It was an approach to playing where it’s so delicate. It’s just the opposite of the ‘in your face’ guitar playing that I used to do. This was the kind of thing that was slippery. It was like you have to hold your breath while you’re playing these solos. You can’t breathe or you’ll throw yourself off.”

3. Rockin’ Chair (The Band, 1969)

“I’m knocked out by older people,” Robertson told Time magazine in 1970. “Just look at their eyes. Hear them talk. They’re not joking. They’ve seen things you’ll never see.” Till this point, rock music had been defined by youth. The Band’s obvious respect for the older generation was genuinely radical. And nowhere was it more apparent than on his poignant-beyond-words “Rockin’ Chair.”

“Rockin’ Chair” transports the listener to another time, with Helm on mandolin, Hudson’s wheezing accordion and some of the finest close-knit harmonies of The Band’s career. Manuel takes the lead, playing the part of an elderly sailor attempting to persuade his best friend, the marvellously named old seadog Ragtime Willie, to finally retire and return home, where the two can see out their remaining years in each other’s company, seeing old friends and telling old jokes. Manuel sings it with such empathy and feeling that it’s scarcely believable that he was just 26 at the time of recording — and a tragedy that he’d never reach the age of the character in the song.

2. The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down (The Band, 1969)

When Robbie Robertson wrote “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” he knew that only Levon Helm could sing it. Born in Elaine, a small town in Phillips County, Arkansas, Helm was the only Southerner in The Band. Without the authority his voice gave, the song, sung from the perspective of Virgil Kane, a former Confederate soldier, wouldn’t have worked at all.

“Levon and I went back the furthest and I thought I understood his instrument better than anybody else,” Robertson told this writer in 2019, “so I tried to the best of my ability to write songs that he could sing better than anybody in the world. When I would play him the songs, he knew that I was writing them for him. He just accepted it in a very natural way and tried to figure out as quickly as possible how to do the song justice. The only thing he told me, when it came to the writing of The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, was, ‘Don’t mention Abraham Lincoln.’”

Click to load video

Robertson took Helm’s advice, but the song has still courted controversy, with some seeing it as a glorification of the Confederate cause. But when heard alongside Robertson’s work of the time, it’s clear that it’s an attempt to truly get under the skin of an ordinary person and understand the human cost of war — the wounded pride, trauma, class and regional divides. It was written as it was becoming clear that the Vietnam War was deeply unpopular in the U.S., not to mention a foreign policy disaster — though it seemed to look to the past, in the way that it showed how ordinary Americans were collateral damage for the rich and powerful, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” was timely.

1. The Weight (Music From Big Pink, 1968)

“The Weight” is The Band’s signature song, on the one hand a secular hymn that speaks of the value of sharing a burden; on the other, a road-weary traveller’s surreal encounters in a town populated by oddball characters. It’s a showcase for The Band’s musicianship, vocal talent, and ability to assimilate country, gospel, blues, and soul, creating music that pays no mind to genre. But according to writer Robbie Robertson, it wasn’t initially in the running to be included on Big Pink.

“After The Basement Tapes, where there was all kinds of imagination and madness involved in some of the songwriting, that loosened up things,” Robertson told writer Steven Hyden’s Celebration Rock podcast in 2018. “When I wrote ‘The Weight’, I thought, ‘Now I’ve gone too far. Nobody’s going to understand this, even me.’ So, it was hard to think, ‘Guys, I’ve written a song here that really could change things or make a difference,’ or anything like that. I thought, ‘It’s too outside the lines here, but we’ll keep it as a back-up in case one of the other songs doesn’t work out.’”

The seed for “The Weight” was planted when beat poet Gregory Corso recommended Robertson visit the famed New York City bookshop, Gotham Book Mart. Ever the cinephile, Robertson was delighted to discover they stocked movie scripts, including Ingmar Bergman’s screenplay for The Seventh Seal, and Luis Buñuel’s scripts for Nazarín and Viridiana.

Images from those scripts stuck with Robertson and, months later, inspired “The Weight.” “One night in Woodstock, upstairs in my house in a workspace next to my bedroom, I picked up my 1951 Martin D-28 acoustic guitar to write a song. I turned the guitar around and looked in the sound hole,” Robertson told the Wall Street Journal in 2018. “There, I saw a label that said ‘Nazareth, Pennsylvania’, the town where Martin was based. For some reason, seeing the word ‘Nazareth’ unlocked a lot of stuff in my head from ‘Nazarin’ and those other film scripts.

Click to load video

“‘Take a load off and put it right on me’” is also pure Buñuel. Once you lend a hand and assume someone else’s burden, you’re involved. ‘Carmen and the devil walkin’ side by side’ is from The Seventh Seal and the chess game with Death.”

The Band’s genius was in turning this song, loaded with arthouse movie references and biblical portent, into a communal anthem, one which became a defining moment of their set at Woodstock and inspired countless cover versions by artists including Aretha Franklin, The Staple Singers, and The Supremes & The Temptations.

“That group, the brotherhood and musical connection between us all was so powerful,” Robertson told this writer in 2019, trying to get to the bottom of what made The Band so special. “Everybody played such an important part in this production, in this movie, in this story — the characters and the way they all fit together, musically and personally. This wasn’t a group where there were a couple of main guys like the singer and the guitar player, and then some other guys back there. That’s why it could be called The Band — because it really was, truly that. The different musicalities of these guys was extraordinary. And the power of that brotherhood and how serious we were at honing the craft and doing something that had meaning and depth to it. We weren’t on a pop cavalcade, our job wasn’t to figure out if people liked us, it was to find a sound, a feeling, a music that goes beyond all of that. We just came in on a different train.”

Order The Band’s The Best of the Band on vinyl now.