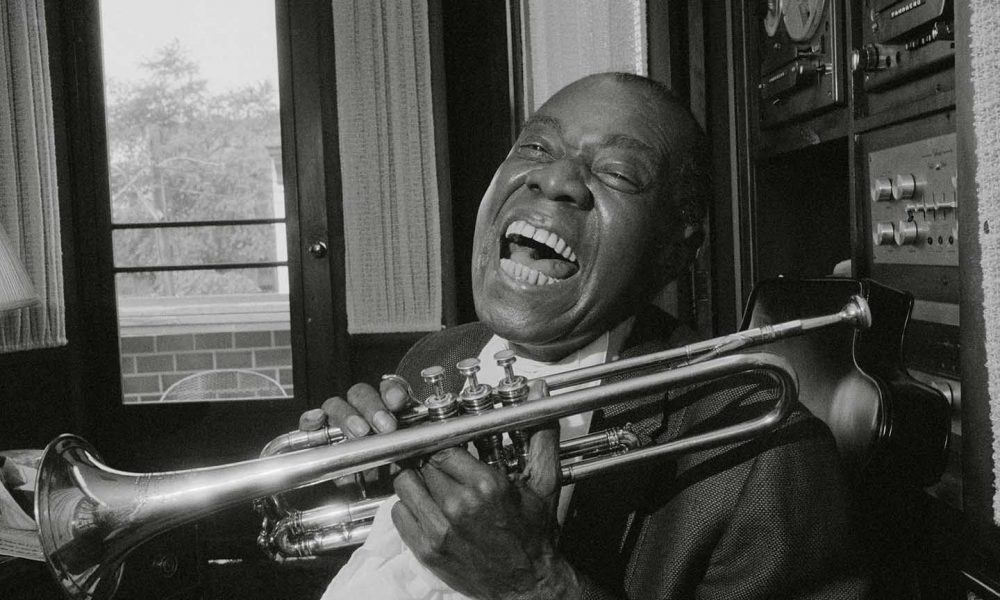

Louis Armstrong in 20 Songs

How do you sum up Louis Armstrong’s career in just 20 songs? We’ve attempted the impossible…and we’ve actually come up short by just listing 19 songs. We’d love to hear from you what song you think we should add? When you’ve all spoken, then we’ll complete Louis Armstrong in 20 Songs.

Making records for Louis Armstrong all began on 5 April 1923 when King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band went to Gennett’s studio to cut the first of 28 sides that were to make history. These were not just Louis Armstrong’s first recordings, but also the first by a black jazz band playing the music that entertained the crowds at Lincoln Gardens.

Among the tunes the band recorded on their first day was ‘Dipper Mouth Blues’, a tune co-written by Oliver and Armstrong and it certainly had considerable significance in that ‘Dipper Mouth’ was Louis’s. It was released a few weeks after the recording and soon began to attract the attention of record buyers.

In June 1924 Louis quit the Oliver band, a few months later, in September, Fletcher Henderson telegraphed Louis asking him to come join his band in New York. Henderson’s was the most prestigious black band in America and for Louis, the only downside, apart from having to leave ‘Lil, his wife in Chicago, was the pay, at $55 per week it was less than Oliver paid him, but the compensation was exposure.

A few weeks after joining the band, at his second session with Henderson, they recorded the wonderful Shanghai Shuffle arranged by band member, clarinettist and saxophonist, Don Redman. Also with Louis in the orchestra at this time was Coleman Hawkins the brilliant tenor saxophonist. For the next year, Louis was in and out of the studio with Henderson’s band on a regular basis.

As well as recording with Henderson’s Orchestra, Louis earned some extra money, and gained valuable experience, working as a session player with others. There were several blues singers he worked with at Columbia, including Alberta Hunter, Virginia Liston and Maggie Jones, as well as Bessie Smith, who was building a big reputation that earned her the title, ‘Empress of the Blues’. Louis played the haunting trumpet refrain on Bessie’s version of St Louis Blues recorded on 25 January 1925.

Louis quit the Henderson Orchestra in October 1925 and having signed to Okeh Records he went into the studio in Chicago and Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five were born. It was on the morning of 12th November 1925 that Louis along with Lil, Kid Ory on trombone, Johnny Dodds on clarinet and Johnny St Cyr, the banjo player recorded ‘Well I’m in the Barrel’, ‘Gut Bucket Blues’ and ‘My Heart’. The first two tunes were the first release by Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five’s on the OKeh label for which he earned $50 a side for each recording and probably a similar amount for the tunes that he and Lil wrote – OKeh sold their records for 75 cents a piece.

Lil and Louis were living at a house on 44th Street on Chicago’s South Side in 1926 and for the remainder of the year, they were kept busy. The Hot Five were back in the studio in the last week of February where Louis managed another first. After recording ‘Georgia Grind’ the band did ‘Heebie Jeebies’ on which Armstrong sang. By the time the second verse came around Louis had dropped the paper on which the lyrics were written. He had no alternative but to improvise and so his trademark ‘scatting’ was heard for the first time.

Scat singing was what it was called in New Orleans and was by no means either an invention of the city’s musicians or by Louis as some have suggested. There’s scat singing on record as far back as 1911 when Gene Greene made ‘King of the Bungaloos’; five years later he was doing similarly on ‘From Here To Shanghai when he did a faux Chinese scat. However, it was Louis that did much to popularize scatting. It’s been suggested that ‘Heebie Jeebies’ sold 40,000 copies, which was a large number for a ‘Race record’ at the time; a sign that it may have crossed over to a white audience.

In May 1927 the Hot Five did become the Hot Seven and the inaugural session was in May 1927 and besides Lil, Johnny Dodds and Johnny St Cyr there was Trombone player Jon Thomas, Pete Briggs on Tuba and Louis’s old friend Baby Dodds on drums. Not only were these sessions marked by the addition of a drummer, but they also have the distinction of being recorded electronically, rather than by the old acoustic process. Louis Armstrong records on OKeh sound a lot better than they did previously.

Three days after the Hot Seven session Louis was back in the studio to record one of his milestone records, the classic, ‘Potato Head Blues.’ A classic in every sense, and according to Woody Allen, one of the things that make life “worth living.” Although not strictly speaking a blues tune it features one of Armstrong’s greatest solos, in the second half, and a superb example of a ‘ride out’ chorus at the end. According to Satchmo, “This is the one that Tallulah Bankhead says is her favourite of all my records – Potato Head Blues. I kinda like this one myself!”

For many jazz aficionados everything that is great about music and Jazz and Louis Armstrong came together on 28 June 1928 when the Hot Five recorded what is one of the landmark recordings of the 20th century – ‘West End Blues’. With Armstrong’s marriage to ‘Lil dissolving, she had been replaced in the band by the brilliant Earl Hines. It is doubtful whether the old Hot Five and certainly Lil, could have pulled off ‘West End Blues’ with the dexterity of the new players. Hines, in particular, is the perfect piano foil for Louis. They had been playing ‘West End Blues’ live at the Savoy Ballroom so all they were doing was transferring their nighttime work to a record – which most artists would struggle to pull off with the excitement that Louis and the others achieve.

One of Louis’s finest recordings from this period is ‘Beau Koo Jack’ recorded on 5 December 1928 as Louis Armstrong and His Ballroom Five – despite, there were six players in addition to Armstrong and including Hines and clarinettist Don Redman. In 1929, ‘The Hottest Trumpet in Chicago’ began to make the transition to the hottest trumpet in America. A significant step on this journey came on 5 March 1929 when Harry Rockwell, OKeh’s recording director in New York put Louis and his Orchestra into the company’s studio on West 45th Street, close to New York City’s Times Square.

‘Knockin’ A Jug’ was one of the two tunes they did that first morning, played by both black and white musicians – Armstrong’s first mixed recording session. Accompanying Louis was Jack Teagarden on Trombone, Happy Caldwell on Tenor sax, Joe Sullivan, piano, Kaiser Marshall on drums and the brilliant Eddie Lang on guitar. This wonderfully exuberant tune was made up in the studio and is the last of what is considered ‘The Hot Fives and Sevens’. It’s a fitting culmination to what went before and acts as a perfect musical end-piece before the change came about,

Pops was in New York City to record as The Louis Armstrong Orchestra, which was in fact pianist Luis Russell along with other members of his band; these were musicians he’d been playing with them at the Savoy Ballroom. Among the tunes that Louis cut for OKeh was a stunning version of ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’ co-written by Fats Waller. Recorded in mid-July 1929 it was taken from the hit production of Hot Chocolates at Connie’s Inn, the Harlem club on 131 Street and 7th Avenue. At Connie’s Louis would reprise the song from the Orchestra pit at the opening of the second half of the show – invariably brought the house down. It would remain one of Louis’s signature pieces throughout his career.

Armstrong was kept buy recording throughout the next few years and in January 1932 Louis recorded a stellar rendition of ‘All of Me’, it was to become his first record to be listed as a Billboard No.1. Shortly after recording this Louis visited Europe and when he returned in late 1932 he did some sessions for RCA Victor that continued for the next couple of years.

In late 1934 Pops’s manager Joe Glaser did a deal with the newly formed Decca Records and despite being less than a year old in America they had already signed Bing Crosby. Jack Kapp, who founded ran Decca in the US only had one thing in mind when his company made records –“Where’s the melody” is what Kapp said to all his artists and to remind them he hung a sign in the Decca studio to remind everyone.

No clearer indication of what was to come from Louis could there be than one of the first songs he recorded for Decca. Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields’s ‘I’m in the Mood For Love’ – it oozed melody and Louis with the Russell band behind him gave it a sheen that had been lacking from most of his records over the past three or four years. Recorded on 3 October 1935 it entered the Billboard chart three weeks later and became one of the top 3 best sellers in America. Louis was back where he needed to be.

For much of the rest of the decade and on through the war years, Louis recorded and toured, but as is the way with pop music his style was not as popular with the general public as it had been. Big bands were the new pop and Pops was old school.

It wasn’t until 1947 that Louis found a way back, and that way, was to go way back and reinvent the sound of New Orleans. In February 1947 Armstrong played Carnegie Hall with a six-piece band led by Edmond Hall – his Café Society Uptown Orchestra. This was the start of the All-Stars. In November 1947 after a string of successful dates, Armstrong played the Symphony Hall in Boston. It was recorded and we’ve chosen ‘Muskrat Ramble‘…joyous music as has ever been recorded.

The All Stars became a big draw over the next few years and as well as recording this group, Decca had the idea of putting Louis in the studio to sing with various orchestras, including one led by the brilliant arranger, Gordon Jenkins and then in July 1951 with Sy Oliver – it was not his full orchestra, just an 8-piece band featuring Billy Kyle on piano, but none of the All-Stars. They recorded ‘A Kiss To Build a Dream On’ that stayed on the Billboard Best Seller list for months. The success encouraged Decca to release ‘When it’s Sleepy Time Down South’, this time with Gordon Jenkins. This was something of a theme tune for Armstrong and it became a Top 20 hit.

In the summer of 1954 Armstrong recorded for Columbia, The man with the idea to make Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy was George Avakian’s and it was inspired. Many of the tracks on the Handy album are extended blows running to five minutes and more. Some biographers have suggested that this was the first time that Louis was given longer than the typical ‘single’ length of three minutes during the making of a record and in so doing Avakian had the vision that Decca did not. This was not the case, as way back in 1950 on Louis’s first Decca LP, New Orleans Days he stretches out on an almost nine-minute version of ‘Bugle Call Rag’. However, that takes nothing away from Avakian and the work that Louis and the All-Stars do on their homage to Handy; we’ve chosen ‘Ole Miss Blues’, for the sheer exuberance of their playing.

In September 1955, Avakian took Louis back into Columbia’s New York Studio to record ‘A Theme from the Threepenny Opera’ – the song most everyone knows as ‘Mack the Knife’. It proved to be Louis’s biggest hit for years when it made the Billboard charts in early 1956, staying there for almost four months.

Over the next decade, Louis and the All Stars toured and recorded and entertained the world, and made some fine records. It wasn’t until 1964 that Louis really made an impression on the singles buying public and when he did it was huge.

On 15 February 1964 ‘Hello Dolly’ entered the Billboard charts at No.76, one place ahead of the Dave Clark Five. Twelve weeks later ‘Hello Dolly’ knocked the Beatles, ‘Can’t Buy Me Love; from the top spot, in doing so it ended fourteen straight weeks of Beatles’ No.1s. ‘Satchmo – Louis was back and back big time.

On 16 August 1967, Bob Thiele, the producer of Satchmo’s LP with Duke Ellington took a demo of a song that he and George Weiss had written; naturally, he took it first to Glaser and then to Louis, who was performing in Washington DC. History has since revealed that Tony Bennett had, first of all, turned the song down flat. History has also shown it to be an enduring song, for Louis, a man in the November of his years, able to nail its sentiments perfectly; the President of ABC-Paramount Records couldn’t have disagreed more, he virtually banned the company from putting any effort into the song and in America it disappeared without trace.

Not so in Britain, where it demonstrated that you cannot keep a hot song down as it progressed steadily up the charts, reaching No.1 in the last week of April 1968 and stayed there for a month, selling well over half a million copies in the process. Today there’s not a person in the world who does not associate this song with Louis Armstrong, whether it’s because they bought it as a single, have it on one of the hundred’s of compilations it’s appeared on, heard it on the soundtrack of Good Morning Vietnam in 1988 or one of probably hundreds of adverts that have used its inspiring message as a sound-bed. It’s a song that familiarity has not found contemptuous, quite simply it’s one of the most uplifting, life-affirming songs of all times – and it’s all because of Louis Armstrong.

It is of course, ‘What A Wonderful World’

This is Louis Armstrong in 20 Songs on Spotify