Ruth Brown, 2016 Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award Winner

This is the first in a news series of Letters from Nola in which Scott Billington, the vice president of A&R for Rounder Records, and a Grammy-winning (seen above with Ruth), New Orleans-based record producer with over 100 albums to his credit, will keep us up to date with all that is great and happening in the Crescent City music scene. Anyone who has visited this amazing city will know that its heart beats to a unique musical rhythm that Scott will help explain over the coming year.

It was a cool February morning, and we were driving through the last of the fallow brown fields of the Mississippi Delta, heading into the kudzu-covered hills around Yazoo City, on Highway 49. In the van with me were singer Ruth Brown; her keyboard player and musical director, Bobby Forrester; and her two sons, Ron Jackson and Earl Swanson. The evening before, at a casino along the river in Greenville, Ruth had performed before an audience of mostly older African-American fans who remembered her as the biggest star in rhythm and blues, in the early 1950s. She put on a show that had everyone dancing in their seats, and if her voice was now grainier than on her early hit records, her timing, wit and charismatic sass left no doubt that she remained a singer and entertainer of undiminished power.

We were on our way to New Orleans, where we would record Ruth’s debut album for Rounder Records. “You know,” said Ms. Brown, “We’re about to leave spiritual territory and head into gospel country.”

I waited a few seconds and asked, “What do you mean by that, Ms. B?”

“Well,” she said, “When our people had no way out of this place, all we could sing about was the next life—crossing that River Jordan. Once we got out, we could celebrate life in the here and now.”

It was that kind of perspective that Ruth Brown brought to her music: an occasionally world-weary acquaintance with the hardships and travails of life, coupled with the determination and resilience to get on with it. On her later recordings on the Fantasy and Rounder/Bullseye Blues labels, on songs such as “Too Little, Too Late” or “A World I Never Made,” she brought grace to songs about sadness and heartache, finding a universal truth that resonated with her audiences. And in songs like the double-entendre “If I Can’t Sell It, I’ll Keep Sittin’ On It,” she carried forth a tradition of humor and stagecraft that is too often missing in live musical performance today.

In 2016, twenty years after her death, Ruth Brown will be awarded her second Grammy as the recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Recording Academy. Looking back at the many stages of her career, it is clear that the honor is well deserved.

In the early 1950s, Brown was the first recording star for Atlantic Records, which has sometimes been called “the house that Ruth built.” In those days, the biggest challenge for an independent record label was getting paid, but Brown’s string of hits, including “Teardrops From My Eyes,” “5-10-15 Hours” and “Mama He Treats Your Daughter Mean,” meant the distributors had to pay Atlantic in order to get her next record. She toured almost without stopping for nearly a decade, sidetracked only once by a serious car accident, even scoring a pop hit with “Lucky Lips” in 1957.

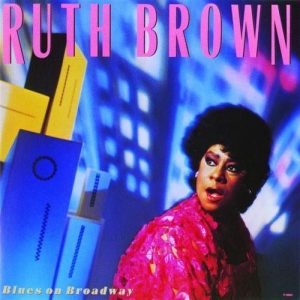

The 1960s were lean years for Brown, as musical tastes changed, but she found her way back into show business as an actress in the 1970s, on television’s Sanford and Son, in the John Waters film Hairspray, in Allen Toussaint’s musical Staggerlee, and in Broadway’s Black and Blue, for which she won a Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical and her first Grammy Award, in 1989, for the related album, Blues on Broadway.

Concurrently, she and attorney Howell Begle began petitioning record companies to institute a standard royalty for legacy rhythm and blues artists, which led the foundation of the Rhythm and Blues Foundation. Seed money from Ahmet Ertegun of Atlantic Records meant the Foundation could provide financial support to artists from the golden era of R&B who had fallen on difficult times.

For much of the remainder of our trip from Mississippi to New Orleans, Ruth told us stories about the triumphs and challenges of touring in the South in the 1950s. When we stopped for lunch at a barbeque joint outside Jackson, Mississippi, she was initially hesitant to go inside, but then quickly relaxed when she realized that we were all welcome.

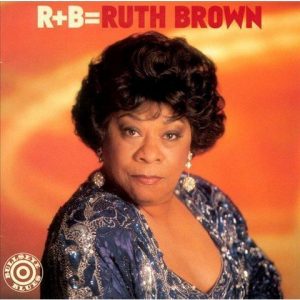

The next day, I picked up Ms. B and crew at their hotel in the French Quarter and drove to Ultrasonic Studio, on the edge of the Gert Town neighborhood of New Orleans. Most of the ten-piece band I had assembled was getting set up in the studio, while engineer David Farrell was fine-tuning sounds and mic placements with drummer Herlin Riley. A great deal of preparation had gone into the sessions, and I had my fingers crossed that everything would click.

About two months beforehand, I had gotten together with Ms. B and pianist Dave Keyes at a small rehearsal studio in New York, bringing with me cassette tapes of songs and song demos that I thought might be good for her. She brought Ketty Lester’s “Love Letters” and “Break It To Me Gently,” which she had learned from Brenda Lee. She was excited about many of the songs, including the Los Lobos song “That Train Don’t Stop Here” and the new Dennis Walker/Alan Mirikitani composition “Too Little, Too Late.” We worked on keys and tempos that suited her, and made rough piano and voice recordings.

My next step was to get together with arrangers Wardell Quezergue and Victor Goines in New Orleans, bringing them our new demos. After discussion about the overall shape of each song, they got to work writing arrangements and hand-copying charts for the band (in the days before there was software to do this!). I was astonished at Mr. Quezergue’s gift. He spread out a sheet of manuscript paper on his kitchen table, struck a tuning fork in C, and began writing with a pencil, hearing every note in his head. His charts were impeccable, and he even wrote out the parts for the drums.

Although I tried not to show it, I was nervous when Ruth stepped up to the microphone for the first song, “That Train Don’t Stop Here.” The band had just run through the chart, and I could see at least a small spark of excitement behind a cool “let’s see if these guys are really going to deliver” wariness. Then, as much like a professional athlete as a musician, she delivered the vocal that you hear on the record, with the band playing, complete with the ad lib “rap” at the end of the song (“…soul train, Coltrane, night train…”). When she came back into the control room, she was glowing. “Baby, we’re gonna have a good time,” she said to me, and we were off and running. Her rapport with Riley, who was in an adjoining booth, was one of playful flirtation throughout the sessions, and I remember everyone laughing when we got each final take—always a sign that the music is transcending the studio environment.

There are times when it makes sense to work on a record one instrument at a time, with the singer coming in at the end, but that was not what I wanted to do with Ruth Brown. Instead, we went for live-in-the-studio performances, always aiming for the moment when the spirit took over. We had the players to pull it off, in addition to Forrester and Riley: guitarist Duke Robillard, bassist James Singleton, and horn players Barney Floyd, Charlie Miller, Delfeayo Marsalis, Wessell Anderson and Ed Petersen. We did a few touchups after cutting each track—adding solos, fixing horn flubs—but what you hear on the record is music that happened in real time. The musicians were awed by Ms. B’s improvisations and her ability to nail each song after only a take or two, and she responded soulfully to their grooves.

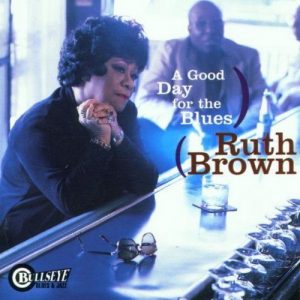

The resulting album, R+B = Ruth Brown, won a Grammy nomination the next year, and I was proud to be Ms. B’s “date” for the ceremony. We went on to make another record in New Orleans for Rounder’s Bullseye Blues imprint, A Good Day for the Blues, which also won a Grammy nomination.

Ruth Brown was an artist and entertainer of the first rank, a singer who communicated joy and heartache in a way that allowed her audiences to celebrate their own lives through her music. She never second-guessed herself. She sang blues, jazz, R&B and pop music with equal aplomb, but no matter what the song, the kind of in-the-moment emotion and engagement she consistently delivered is something that cannot be manufactured by tweaking and overdubbing in the recording studio, and it is a palpable presence on record. I learned from her that there is no substitute for that kind of talent, and, indeed, how rare that kind of talent is. The Recording Academy has done well to recognize her.

Photo credits, The header image is by Barbara Roberds. The top photo in the feature is by Shonna Valeska