Psychedelic Blues: When The Blues Turned On And Tuned In

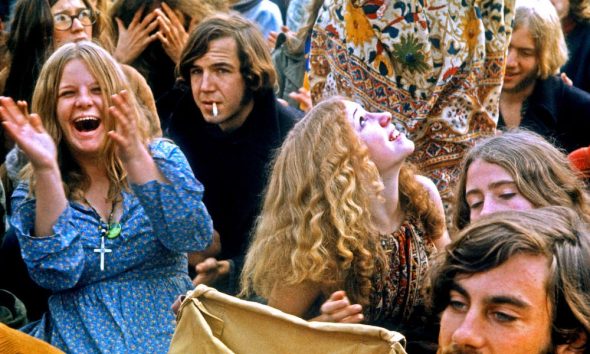

When African-American innovators of the 50s met Black Power and Flower Power head on, the psychedelic blues was born.

After psychedelia came to a boil in the late 60s, the blues and rock heroes of the 50s took a brief but thrilling walk on the wild side, with fuzz guitars, wah-wah effects, and epic jams to the fore. It was the Age of Aquarius, and the blues was busy being psychedelicized. The psychedelic blues period for Chicago titans like Muddy and Wolf and first-generation rock’n’rollers like Bo, Chuck Berry, and Little Richard wasn’t a long one but it blasted a hole in preconceptions on either side of the stylistic fence. And the impact was as unforeseen as it was long-lasting.

Giving the greats their due

Baby boomer rockers and Chicago blues originators spent a good portion of the 60s doing a dizzying do-si-do together. By mid-decade, the UK and US rock stars who’d learned their lessons from the old-schoolers’ 50s recordings did their heroes a good turn by bringing the spotlight back to them. British Invasion covers of classics from the Chess and Sun catalogs rallied a new audience, leading to reissues and new releases from the bluesmen marketed to the younger crowd.

But by the late 60s, the countercultural explosion had pulled rock fans further from away the genre’s musical roots, so a few savvy souls decided to do something about it.

The train started rolling in the mind of Marshall Chess, son of Chess Records co-founder Leonard Chess. The label had taught the world to love Chicago blues, but by 1967, twentysomething Marshall reckoned his dad’s company had to catch up or get left behind. With this in mind, he created Chess’s Cadet Concept imprint, initially designed to capture the attention of the “kids” with heady psych/soul/jazz hybrid The Rotary Connection (including a young Minnie Riperton) and rockers on the rise like Status Quo (the label hosted their lone U.S. hit, “Pictures of Matchstick Men”) and The Wildweeds.

But barely an eye blink later, Marshall was concocting a plan to swing some of that cool cred over to Chess Records’ blues barons. First up was Muddy Waters himself. Muddy was none too eager to get a paisley-powered makeover. But he trusted Marshall enough to leave his regular band at home for 1968 sessions overseen by Marshall, saxophonist/arranger Gene Barge, Rotary Connection leader Charles Stepney and populated by players from the Connection’s axis, including jazz guitarists Phil Upchurch, Roland Faulkner, and Pete Cosey (who was also a part of Miles Davis’ 70s fusion period).

Waist Deep in ‘Electric Mud’

Egged on by Stepney, Barge, and Chess, the jazzers led a reluctant blues legend into heavy psychedelic rock territory. It should have been a disaster. For a while, Muddy thought it was. But Electric Mud tapped into something vital and visionary. Up till then, “blues-rock” usually meant white kids copying their blues heroes. At a time when you could tally African-American rockers on one hand and still have two fingers to spare for a peace sign, here was a room full of Black men stirring up a thunderstorm of fuzz and wah-wah guitars, nail-gun drum beats, and blazing organ, all in the service of the godfather of Chicago blues. In the center of the 1968 civil rights maelstrom (Martin Luther King’s assassination was just weeks before the sessions), it was as much a statement about identity and Black power as a stylistic innovation.

Most of the tracks were rebooted versions of staples from Muddy’s repertoire, like “Mannish Boy,” “(I’m Your) Hoochie Coochie Man,” and “I Just Want to Make Love to You.” But they were awash in crushingly heavy rock riffs that cast the classic tunes in a new light. There were only two non-blues songs: Muddy’s magisterial rumble rules a Cream-like, fuzz guitar-fronted version of “Let’s Spend the Night Together” by The Rolling Stones (who’d taken their name from a Muddy lyric and covered his music) that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on Cream’s Disraeli Gears and “Herbert Harper’s Free Press News.” The latter, written by Sidney Barnes and Robert Thurston, is a straight-up social commentary on politics, the Vietnam War, and the turbulence of the times, shot through with fire-alarm guitar licks and a fat, funky groove. Jimi Hendrix’s assistant would later tell Cosey that the guitar hero would listen to the track for pre-show fortification.

More than a psych-blues experiment

In 1968, Electric Mud was the leading cause of blues purists tearing their hair out, but it did exactly what Marshall intended, becoming Muddy’s first album to appear on Billboard’s Top 200 chart. Sufficiently emboldened, Chess spun his barber chair around and lined up Howlin’ Wolf as the next customer for hip-ification treatment. Calling on the same crew of producers and players, the result was 1969’s psychedelic blues classic, The Howlin’ Wolf Album.

You don’t have to look further than the front cover for proof that Wolf was more skeptical of the prospect than Muddy had been. It declares in unabashedly titanic type, “This is Howlin’ Wolf’s new album. He doesn’t like it. He didn’t like his electric guitar at first either.” The artist’s misgivings notwithstanding, the band that gave Muddy’s fortunes a boost made a slamming, psychedelic meal of Wolf’s canon.

Not only do the musicians slather Wolf biggies like “Evil,” “Down in the Bottom,” and “Back Door Man” with a Chicago-hardened version of San Francisco electric sunshine, they even do a little deconstruction, subverting the contours of tunes like “Little Red Rooster” (here retitled “The Red Rooster”) and “Tail Dragger” for a trippy, funhouse mirror effect. Wolf comes off like a cousin to Captain Beefheart with a wah-wah-soaked acid-rock update of blues standard “Spoonful.” The open-ended frame of Wolf’s 1956 hit “Smokestack Lightning” allowed for the furthest-out feel of all, eventually becoming an echo-laden, fractal eruption.

The blues had a baby and they called it rock’n’roll

Cadet Concept didn’t have a monopoly on Marshall Chess’s revivification plan. All of Chuck Berry’s success came while he was on Chess, but in the late 60s, he briefly jumped to Mercury, where he made 1969’s Concerto in B. Goode. Berry was more inclined to keep his finger on the pulse of the rock’n’roll audience he helped create, and his flirtation with hippie culture was probably the most far-flung of all.

Berry had already dipped a toe into the water with his previous album, 1968’s From St. Louie to Frisco, by working with The Sir Douglas Quintet, except for the absolutely bonkers “Oh Captain” and the head-trip album art, the results were still fairly traditional. So was the first side of Concerto in B. Goode, other than a few flurries of wah-wah guitar. But the album’s second side was occupied entirely by the nearly 19-minute instrumental title track. Buoyed by his young guitarist Billy Peek, who would go on to replace Ronnie Wood in Rod Stewart’s band, Berry dives into an epic, mostly modal jam in which the psychedelic effects flow freely.

Back in the Chess realm, Bo Diddley – whose entire career so far had been on the label’s Checker imprint – was ready to reach out too. The rock’n’roll pioneer never abandoned his blues roots, and his last couple of albums had been all-star sessions with Muddy, Wolf, and Little Walter, but in 1970 the man who brought a new beat (and a rectangular guitar) to rock became the next Chicago heavyweight to take a stab at turning on and tuning in, if not quite dropping out.

Released on Checker rather than Cadet Concept, which was nearing the end of its run, The Black Gladiator put a fresh coat of fluorescent DayGlo paint on Bo’s sound. Bo stares wild-eyed from the back cover with leather belts strapped across his bare torso, looking like a cross between an ancient warrior and Bootsy Collins. The liner notes call out his influence on “today’s ‘with it’ groups”, while the distorted guitar and in-your-face organ give Bo an undeniably of-the-moment sound himself. Unlike Muddy and Wolf, Bo cut all new tunes for his big crossover bid (though “You, Bo Diddley” is a close cousin to “Hey Bo Diddley”). Instead of yoking his trademark riffs to pounding rock beats like his Chess brethren, he goes for a funked-up feel throughout much of the record, coming off like James Brown jamming with Sly & The Family Stone.

It wasn’t only the album’s musical direction that was bold. The record was cut when the campaign to release Black Panther Huey Newton from prison was at full throttle and race relations in America were a proverbial powder keg. An African American declaring himself a Black Gladiator and striking a martial pose (albeit with guitar) on the album cover was not an unprovocative statement.

By this time Bo’s fellow rock’n’roll originator Little Richard was stretching out and feeling the funk too. His 1970 album The Rill Thing was made with the now-legendary house band at Muscle Shoals, Alabama’s FAME Studios. It mostly splits time between swampy funk and sweaty, Stax-style soul, plus some screaming lead guitar out of the Quicksilver Messenger Service playbook. Rabble-rousing “Freedom Blues,” with Nixon-bashing lines like “Let’s get rid of that old man… and bring our government up to date,” was Richard’s closest thing to a hit single since the 50s. But Richard really let it all hang out on the 10-and-a-half-minute title track, an exploratory funk jam with electric piano, sax, and growling guitar vying for prominence.

After the explosion

Following the initial experiment, the blues and rock’n’roll pioneers who tried on a hip new set of threads wore them for another album or two at most. Then in 1972-3, Chess set up a series of London Sessions albums that spun the dance partners around yet again, with British rock stars like Eric Clapton and various Stones and Beatles backing their heroes on reverent versions of classic blues tunes. By the mid-70s Muddy, Wolf, and company had mostly moved back to working in more straight-up settings with their old cohorts.

At the time, some critics and hidebound traditionalists were perplexed by this collision of cultures, but down through the decades, the full impact of these records revealed itself. Electric Mud was celebrated in Martin Scorsese’s 2003 documentary The Blues, where Public Enemy’s Chuck D and others affirmed its influence and participated in a tribute. “Herbert Harper’s Free Press News” was covered by Lucky Peterson and others. And latter-day reissues of the records have solidified their cult-classic status.

In the long view, the psychedelic phases of these musical giants may have been a blip on the screen. But those brief moments burned brightly and boldly. And the statements they made about African-American empowerment in an embattled era are no less relevant half a century later.

Peter Cranford

July 17, 2020 at 5:38 pm

Man, how was Howlin’ Wolf able to blues recordings for all those years without a flute? This is like putting whipped cream on top of soul food …